Outside Lands Music Festival, Golden Gate Park

Last weekend I attended the three-day Outside Lands Music Festival held in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. I don’t go see as much live music as I did in my younger days (e.g., 25 Phish shows during the mid to late ’90s thank you very much) so I saw more live music in these three days than the whole last year combined (which is a little sad).

On Friday, we headed to the main stage and caught the UK reggae band Steel Pulse followed by the highly energetic Manu Chao. The headliner on this stage Friday night was Radiohead. I’ve grown to like their music more and more over the years but until Friday had never seen them live. I was completely blown away … these guys are absolutely mesmerizing. I loved it.

We spent most of Saturday camped out at one of the several ‘side’ stages and watched the bluegrassy/folky (with Chinese flavor) music of Abigail Washburn (w/ Bela Fleck), followed by the highly entertaining Devendra Banhart. Before his set was done, I headed over to the main stage to catch most of the New Orleans funk band Galactic (featuring horns from the Dirty Dozen Brass Band and Cyril Neville on vocals). I made it back to our spot on the other stage to see Regina Spektor. The quirky and endlessly fun Cake followed and then we topped it off with a little bit of Tom Petty on the way out.

Sunday was my favorite day of the whole weekend. We got their early and camped out at the ‘Twin Peaks’ stage the whole day. I also brought my camera that day. Here are some photographs from Sunday with descriptions below the photo.

I thought the organizers of the festival did a great job in terms of layout and other logistics. There’s always something to complain about when you put so many people in a relatively small space, but all-in-all it was good (I’ve been to much worse). Golden Gate Park has many lawn areas that are separated by beautiful groves of trees, so there was some ‘bottle-necking’ trying to get between, but I’m not sure how they could’ve avoided that unless they cut down trees.

The first act of the day on the ‘Twin Peaks’ stage was San Francisco’s own ALO. These guys were funky and jammy … I loved it, a great way to start off the day.

Next up was the Canadian indie/pop band Stars. These guys weren’t quite my cup of tea, but entertaining nonetheless.

One of my favorite sets of the whole weekend was Andrew Bird. Not only does can this guy play any instrument (including virtuoso whistling skills), his music is interesting and entertaining. He and the drummer made great use of technology by recording themselves on the fly, looping it, and then playing complementary phrases over it. Sometimes that technique can be obtrusive but they did it very well.

The Canadian indie-rock supergroup Broken Social Scene was up next and they rocked! This was another band I’ve heard of but never saw live. Fantastic live show. At one point there seemed to be about 10 people up on stage but the music never got chaotic (like I’ve seen happen with giant groups like that).

Last up on this stage for the day was one of my favorites, Wilco. I have seen these guys a few times and listen to them all the time. In my opinion, they are one of America’s best rock bands right now (the Beatles of our time?). It got a lot more crowded for this set and this photo of songwriter and band leader, Jeff Tweedy, between a bunch of heads was the best I could get. They played a great set as the sun set on the park, including a lot of my favorites (e.g., ‘California Stars’, ‘Hate It Here’, ‘Jesus, etc.’, and ‘Hummingbird’).

It’s been almost a week since this festival ended and now I’m feeling some live music withdrawal … I’m gonna have to fix that soon.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Friday Field Foto #61: Hummocky cross stratification

This week’s Friday Field Foto highlights everybody’s favorite oscillatory-/combined-flow sedimentary structure … hummocky cross stratification!

I have to apologize for not having the specific location and formation information for this photograph. I took this several years ago – before I became anal-retentive about my geologic photography. I do know that it is in the Upper Cretaceous (~70-90 million yrs ago) of westernmost Colorado (not too far from the town of Rangely … maybe the Sego Sandstone, I don’t know).

Hummocky cross stratification, also known as HCS, is very cool … everybody gets excited when they see a good example. Check out the front page the blog The Dynamic Earth for an even better shot (also in the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway succession). One of the key recognition criteria is the convex-up, mounded shape (going up from left to right in the photo; click on it for larger version).

Some of the nitty-gritty details about the formation of this sedimentary structure are still discussed and debated but, in general, it is thought to be formed by a combination of oscillatory flow (i.e., from waves going back and forth) with unidirectional currents that entrain sediment. I’ll leave it at that for now, but check out Myrow & Southard (1991) for more.

Another reason people get excited when they see HCS is that it’s a fantastic indicator of a particular environment — a subaqueous environment shallow enough to feel the effects of waves. Some also think this structure is indicative of particularly strong wave action associated with big storms. You will typically find them in a stratigraphic succession sandwiched between offshore shale/siltstone and shoreface and/or delta-front deposits.

–

Myrow, P.M. and Southard, J.B., 1991, Combined-flow model for vertical stratification sequences in shallow marine storm-deposited beds: Journal of Sedimentary Research, v. 61, p. 202-210.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Papers I’m reading – August 2008

Continuing on with the monthly theme of what peer-reviewed papers I am reading (or planning to read).

Here’s the list for August:

Check out June and July as well.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Geologic field work as a connection to nature

I got really excited when I saw Callan’s idea for this month’s The Accretionary Wedge geoscience blog carnival.

How about ‘geology as connector science’ as a theme? The challenge for writers is to explore their own sense of connection to the planet Earth. I want to hear from geologists about their physical insights, chemical insights, biological insights, anthropological insights, etc.

You can read Callan’s own thoughts on this theme and find links to everybody else’s posts for the carnival here.

At first, I started thinking about how the discipline of geology is connected to other disciplines in science … how the physics, chemistry, biology, etc. of our planet is investigated within the context of a geologic framework. How it’s so much more than simply sticking the prefix ‘geo’ on other disciplines.

But, then I decided to take this post a different direction. Instead of talking about the connection the discipline of geology provides to other sciences, I’d like to post about how effective geology is at connecting one to nature. I’m not talking about some warm and fuzzy, new-agey one-with-nature thing here … I’m referring to the real, tangible connection to the ‘messiness’ of nature’s processes and products.

The best way to experience this connection is to go out in the field and stumble around (literally and intellectually). I’ve always loved this quote about doing fieldwork from Robert Frodeman’s 2003 book Geo-Logic: Breaking Ground Between Philosophy and the Earth Sciences:

Science in the field proceeds at a different rhythm…while the lab narrows and controls the flow of information, the field’s perceptual and conceptual kaleidoscope exceeds our capacities to sort, test, and categorize it. Field scientists develop intuitive skills for parsing knowledge in implicit, nonpropositional ways.

I’ll never forget my first “real” experience in the field … not on a field trip, but doing field work (huge difference!). It was at field camp and one of the professors literally had to put the pencil in my hand and draw the line on the map for me. I’ll never forget that. I was so consumed by the complexity (and beauty) of the geology literally surrounding me that I didn’t quite have the guts to take that step and put the line on the map. I didn’t have that connection yet.

As I became more confident the connection to geology in the field strengthened. Being more confident doesn’t necessarily mean doing it correctly all the time. In fact, by doing more field work, you end up being at least partially wrong almost all the time. Ideally, the degree of ‘wrongness’ diminishes over time but never really goes away completely, which is actually another key aspect of this connection. There’s always something unique when examining what nature produces. There’s always a degree of uncertainty. Having the ability to peer through that uncertainty and conclude something meaningful — to find something significant to compare and contrast with another place or time is what a strong connection allows.

In addition to the connection to nature’s geological products, field work allows a more general connection to nature to develop. Traveling to and camping out in the field is an experience in and of itself. Your brain must deal with the here and now (e.g., logistics, weather, gear, food, water, group dynamics, hazardous plants/animals/locals, etc.) while, at the same time, you keep your mind focused on putting together the pieces of an ancient puzzle. Not always an easy task and sometimes not necessarily ‘fun’ — but memorable and rewarding for sure.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sea-Floor Sunday #27: Sand waves in the Chukchi Borderland

This week’s Sea-Floor Sunday post is very quick … I’ve been busy all weekend with this.

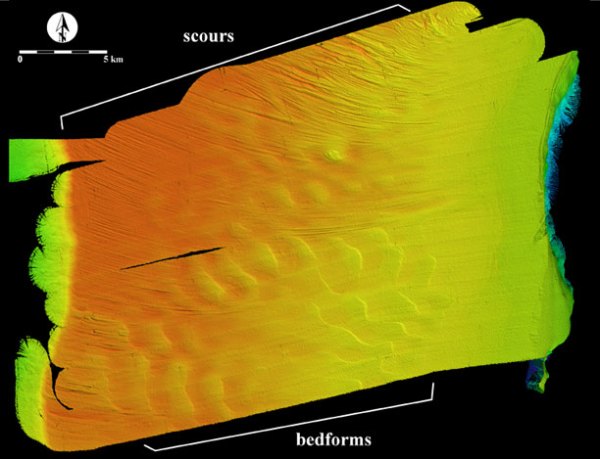

This week’s image highlights some huge bedforms on the sea floor in an area called the Chukchi Borderlands, which is north of the Bering Straight in the Arctic Ocean.

image from http://ccom.unh.edu

Here’s the blurb directly from the CCOM-JHC website:

Map view of a 300 km2 area of the surface of Chukchi Cap. The bedforms are asymmetrical, have wave heights of 10 to 15 m and wavelengths of 2 to 2.5 km. The orientation of the bedforms suggest a strong current flowing from NE to SW across the cap. The scours are 2- to 6-m deep and curved. The scours appear to terminate at ~430 m present water depth. Water depth range in image 400m to 1400m.

This site discusses the various currents in this topographically-complex area that are responsible for ocean water exchange between the Pacific and Arctic oceans.

I’ve post about both sea-floor bedforms (sometimes called sand waves) and scour features before here and here, respectively.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Incredible image of Enceladus

Callan already did this, but I can’t resist … check out this amazing mosaic of Enceladus (moon of Saturn) captured by the Cassini spacecraft.

Credit: NASA / JPL / SSI

Learn all about this image over at the Planetary Society Weblog. Here’s a short blurb:

In an amazingly quick piece of work, the imaging team has already assembled the 8-frame mosaic captured by Cassini as it receded from its close encounter with Enceladus last week. This is a really difficult piece of work. There are 32 separate camera images in this mosaic — 8 high-resolution images taken through a clear filter to get the detail, and 24 taken at half the resolution through ultraviolet, green, and infrared filters to get the color.

This one is zoomed in a bit … these patterns are absolutely stunning!

Credit: NASA / JPL / SSI

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Friday Field Foto #60: Chunk of microbialite in mudstone

My recent trip to the Canadian Rockies to look at some Neoproterozoic turbidites is still very fresh in my mind so it will be part of this week’s Friday Field Foto series.

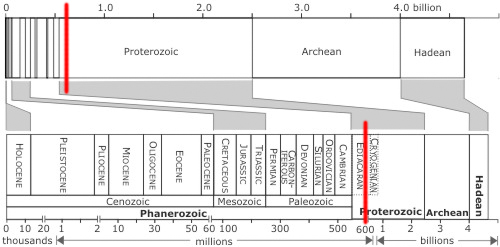

First of all … when is the Neoproterozoic? Note the red line on the figure below, which is Chris Rowan’s handy-dandy time scale (read interesting discussions about this here and here).

One of coolest things about studying ancient sedimentary deposits is thinking about the material that makes up the sediment. Where did it come from? What can it tell us? More often than not, this means taking a look at the composition and/or age of sand grains or the bulk geochemistry of the mudstone. If you’re lucky enough to have material bigger than sand-sized grains then it gets a bit more fun because of the potential to see internal features.

The photo below shows a chunk of carbonate within mudstone (note toe of boot for scale at bottom). Click on it for a higher-resolution version.

The photo below zooms in a bit so you can see the laminated structure. A lamina is simply a very thin sedimentary bed (less than a couple centimeters thick). The laminae are not very distinct, but if you squint your eyes you should be able to see a crude layering (slightly tilted to the right).

So, what is this rock all about?

Well … to be perfectly honest, I did not spend any time researching this specfic rock. Everything I say here is from the researchers that were showing us around (if someone is truly interested in these specific rocks I will track down some real references … let me know in the comments).

The basic interpretation is that the crude lamination originates from microbial mats. The ‘living’ mats trap and bind sediment, successive layers stack over time, and when the organic matter decays this laminated structure remains. What’s cool is that these chunks that were transported off the shelf into the marine basin are all that’s left of it. That is, in this area, only the slope and basinal deposits have been preserved … the shelfal environments were eroded away long ago.

One thing to note is that although the age of the sedimentary succession is ~600 Ma (give or take several million years), the age of the clast itself is not very well known. In this case, we were told that it’s been interpreted to be generally equivalent in age.

Happy Friday!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Neoproterozoic turbidites in the Canadian Rockies

Most of you know that I’m a big fat nerd when it comes to deep-marine turbidity currents* and the sedimentary deposits they create – turbidites (e.g., here, here, here, and here). In fact, my current employer recruited and hired me because of my turbidite nerdiness. As a result, I spend a lot of my time investigating and examining various turbidite systems. Sometimes these systems are still active and on the modern sea-floor, sometimes they are buried deep in sedimentary basins, and sometimes they’ve been buried, subsequently uplifted and are now exposed in mountains.

Last week I had the opportunity to go visit some outcrops in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia. A Canadian researcher and his students have been working on these rocks for several years and were kind enough to show us around for a few days during their field season. For this post, I’m going to discuss very general aspects of the system and show some photographs. If you want to get into the real sedimentological nitty-gritty I’ve included citations for papers they’ve published at the bottom of the post.

We flew into Calgary, Alberta and spent a good part of a day driving to the town of McBride, BC. You can do it in about 6 hours, but we stopped along the way to see some of the sites in this beautiful part of the world.

If you haven’t already been there, you’ve probably heard of and seen photographs of Lake Louise (above). It’s right off the road and there’s a huge hotel there so it’s a popular tourist spot.

At the recommendation of the researcher studying the rocks we were going to see, we stopped at a railroad cut along the way (above) that is interpreted to be roughly time-equivalent to the rocks at the main field site. Looking at rocks along railroad cuts always reminds me of my undergrad days back in the eastern United States.

We made it to McBride later that day and spent the night in a motel there. The next morning we made our way up to their campsite. The photo above is my tent, which is still hangin’ in there after four field seasons in Patagonia weather. We were staying with a group of about 10 or so students who were living up there for seven weeks.

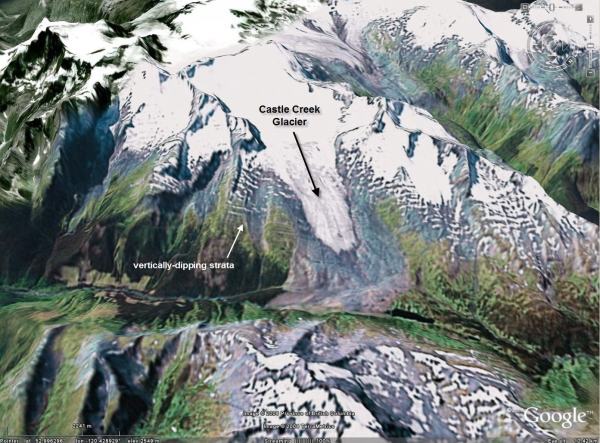

The image above is a perspective image from GoogleEarth showing the unique set up for these strata. The rocks, which are latest Neoproterozoic (~600 million yrs old), are dipping vertically on the steep limb of an asymmetric anticline. The Castle Creek Glacier has cleaned and polished the rocks such that the exposures are extremely high quality. There was a separate group of Canadian scientists up there studying the glacier and they told us that the glacier has been retreating since the Little Ice Age (but the rate of retreat has certainly increased in the last century).

The strata we were looking at are part of the Windermere supergroup, which is a belt of Neoproterozoic rocks in the North American Cordillera that extends from Alaska to the northern United States (and then in localized areas further south). The strata of interest are interpreted to have been deposited along the western passive margin of the paleo-landmass of Laurentia (which is North America essentially) following the breakup of the supercontinent of Rodinia (Pangea is the more famous supercontinent, but is really just the most recent in the Wilson Cycle).

From a distance, outcrops of turbidite systems are generally expressed as interbedded mudstone/siltstone and sandstone. Some sections can be mostly sandstone, some can be dominated by mudstone/siltstone, and then everything in between. Note in the photo above the coarser-grained and lighter-colored sandstone packages amongst the darker mudstone intervals (stratigraphic ‘up’ is to the left). What is great about this outcrop is the quality of exposure of the fine-grained rocks. Mudstones and siltstones are typically covered by vegetation and/or talus. Since these rocks are in the process of being glaciated, the only cover is some patches of glacial debris.

The photo above shows a sandier part of the section which is a bit down-section from the previous photo (again, stratigraphic ‘up’ to the left). The cool thing about vertically-dipping strata is that you can examine lateral relationships by simply walking the beds out … and in this outcrop, one can walk out individual beds for 100s of meters.

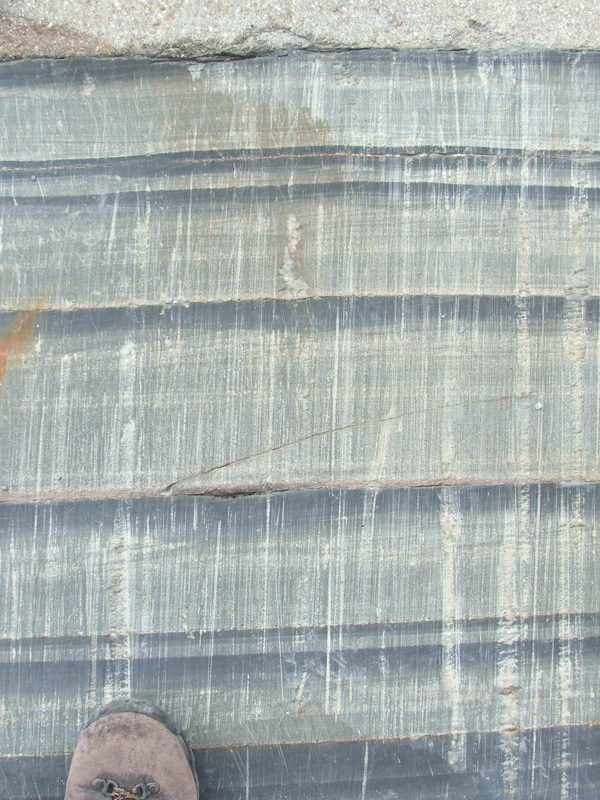

Zooming in a bit more, the photo above (with the toe of my boot for scale) shows some very nice ‘classic’ turbidites. First, you’ll have to look through the prominent vertical streaks (those are the very recent glacial striations). The lighter colors are coarser (fine sandstone) and the darker colors are finer (siltstone). There are several fining-upward beds showing many of the divisions of the ‘Bouma sequence‘, which is the idealized turbidite sequence. Even though these rocks are slightly metamorphosed, the sedimentary structures are beautifully preserved (note the ripple cross-lamination near the top of the middle bed).

I have tons more photographs and will be putting together more posts about these rocks over the coming weeks.

–

Schwarz, E. and R.W.C. Arnott, 2007, Anatomy and evolution of a slope channel-complex set (Neoproterozoic Isaac Formation, Windermere Supergroup, Southern Canadian Cordillera): Implications for reservoir characterization. Journal of Sedimentary Research, v. 77, p. 89-109.

Ross, G.M. and Arnott, R.W.C, 2008, Regional Geology of the Windermere Supergroup, Southern Canadian Cordillera and Stratigraphic Setting of the Castle Creek Study Area in Nilsen, T., Shew, R., Steffens, G. and Studlick, J., eds., Atlas of Deep-Water Outcrops, AAPG Studies in Geology # 56. Chapter H, CD-Room version.

Meyer, L. and Ross, G.M., in press, Channelized Lobe and Sheet Sandstones of the Upper Kaza Group Basin-Floor Turbidite System (Windermere Supergroup), British Columbia, Canada in Nilsen, T., Shew, R., Steffens, G. and Studlick, J., eds., Atlas of Deep-Water Outcrops, AAPG Studies in Geology # 56. Chapter J, CD-Room version.

–

*