A couple items about The Accretionary Wedge

The first edition of the geology blog carnival, The Accretionary Wedge, was published a few weeks ago and turned out to be pretty successful. It still gets page views nearly every day.

The first thing I wanted to point out is that Ron, of Geology Home Companion Blog fame submitted his entry to TAW #1, which was titled ‘Why I Study Geology’. Go check it out at the TAW website here.

Secondly, is it time to start thinking about organizing TAW #2? I’ll happily submit something, but I’m gonna have to bow out of putting this one together…I got that dang dissertation to finish.

Any takers?

Use this post on the TAW site to discuss ideas…let’s try and keep this going!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Some photos from recent field trip to Texas and New Mexico

Many of you know that I was away from blogging for the last couple weeks because I was on a geology field trip. This was my last field trip as a student…sniff sniff. We went to west Texas and southern New Mexico to look at a variety of things ranging from Cambrian sandstones, to Permian reefs, to Pleistocene volcaniclastics. I will post more about the geology soon…in the meantime here are some pretty photos.

The captions are below the photo.

Hiking in the Franklin Mountains to look at the Cambrian Bliss Sandstone.

The Permian Reef Trail in Guadalupe Mts National Park switchbacks up the mountain at McKittrick Canyon.

The view from my tent for four mornings at Pine Springs campground in Guadalupe Mts National Park.

A rainbow over El Capitan along the western escarpment of the Guadalupe Mountains.

Speleothem deposits in Carlsbad Caverns.

Hiking in Alamo Canyon in the Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico.

Ripples at White Sands National Monument (the sand is gypsum!).

Sunset over the San Andres Mountains from Oliver Lee State Park near Alamogordo, New Mexico.

Stay tuned for more photos of specific geologic features.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Friday Field Foto #30: Cross section in a gravel quarry

A few years back, when I was doing my master’s in Colorado, we went to a gravel quarry for the clastic sedimentology class I was taking. They were quarrying very recent fluvial sediments laid down by the South Platte River, which provided some great cross-sectional views of the deposits.

Note the distinct surface separating the underlying red-brown sediments from the overlying, more buff-colored and much more poorly sorted sediments. The entire quarry was full of the deposits of sand-gravel bar formation indicative of a river with relatively flashy discharge.

I love being able to observe the products of very recent geologic processes. It helps make the all-important connection when observing the products of ancient processes.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Science podcasts

This post is a re-run from several months ago.

I take a commuter train nearly every day from home to my office at school. I find this time perfect for catching up on the latest science news via podcasts. Below are science-related podcasts that I subscribe to. If you know of any others, please let me know…i’m always looking for something new.

I’m including the link to the website for these podcasts but, if you use an iPod, you can also easily find them through the iTunes directory. These are all free.

—————————————————

Nature Podcast: This is one of the longer ones at about 25-30 minutes and is published once a week. This podcast sums up 3 or 4 of the prominent articles that are reported in the weekly journal Nature. The format is typically a phone interview with one or more of the authors of a study in that week’s issue. This is the most technical of all the podcasts listed here.

Nature Podcast: This is one of the longer ones at about 25-30 minutes and is published once a week. This podcast sums up 3 or 4 of the prominent articles that are reported in the weekly journal Nature. The format is typically a phone interview with one or more of the authors of a study in that week’s issue. This is the most technical of all the podcasts listed here.

Science Friday: This is one of my personal favorites. Science Friday is part of NPR‘s Talk of the Nation programming and hosted by Ira Flatow. If you listen to this on the radio is an hour long and typically broken into 2-4 segment covering different topics. The podcast edition is delivered so that each segment is a separate episode, which is nice so you don’t have to listen to the entire hour to hear the topic you are really interested in. Sometimes a segment can be over 30 minutes and others will be only 10 minutes. It is very non-technical and Flatow does a great job of keeping the guests from using too much jargon. Lately, they’ve had a lot of climate science and/or policy topics that are pretty good.

Science Friday: This is one of my personal favorites. Science Friday is part of NPR‘s Talk of the Nation programming and hosted by Ira Flatow. If you listen to this on the radio is an hour long and typically broken into 2-4 segment covering different topics. The podcast edition is delivered so that each segment is a separate episode, which is nice so you don’t have to listen to the entire hour to hear the topic you are really interested in. Sometimes a segment can be over 30 minutes and others will be only 10 minutes. It is very non-technical and Flatow does a great job of keeping the guests from using too much jargon. Lately, they’ve had a lot of climate science and/or policy topics that are pretty good.

Science Times is hosted by David Corcoran of the New York Times. It is published once a week and summarizes the main articles that were highlighted in the newspaper that week. This is a nice one to add to the mix because they tend to not focus on the same story that all the other media outlets picked up (usually from Nature or Science). It is typically 15-20 minutes in length.

Science Times is hosted by David Corcoran of the New York Times. It is published once a week and summarizes the main articles that were highlighted in the newspaper that week. This is a nice one to add to the mix because they tend to not focus on the same story that all the other media outlets picked up (usually from Nature or Science). It is typically 15-20 minutes in length.

Science Talk is the podcast associated with the magazine Scientific American. I’ve only started listening to this one recently, but so far so good. There is a little overlap with the others but sometimes that is nice because you get a slightly different perspective or style of reporting. It is similar in length to the others (20-25 minutes) and published about once a week.

Science Talk is the podcast associated with the magazine Scientific American. I’ve only started listening to this one recently, but so far so good. There is a little overlap with the others but sometimes that is nice because you get a slightly different perspective or style of reporting. It is similar in length to the others (20-25 minutes) and published about once a week.

PopSci Podcast is hosted by Jonathan Coulton and is the less serious one thrown on this list. It is associated with Popular Science magazine, which I don’t read, and is essentially a nerdy comedy podcast sprinkled with some information. It is short (<10 minutes) and consists of an intro and summary by Coulton (who is stationed on the moon) and a phone interview with a researcher usually on something offbeat. For example, they once had a guy who studied how fruit flies fight and another story about how San Francisco wants to try and collect dog poo and turn it into energy. The problem is there hasn’t been a new episode in a couple months, so i’m not sure what’s up with it.

PopSci Podcast is hosted by Jonathan Coulton and is the less serious one thrown on this list. It is associated with Popular Science magazine, which I don’t read, and is essentially a nerdy comedy podcast sprinkled with some information. It is short (<10 minutes) and consists of an intro and summary by Coulton (who is stationed on the moon) and a phone interview with a researcher usually on something offbeat. For example, they once had a guy who studied how fruit flies fight and another story about how San Francisco wants to try and collect dog poo and turn it into energy. The problem is there hasn’t been a new episode in a couple months, so i’m not sure what’s up with it.

If you know of other podcasts that are similar to these, please leave a comment and link.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

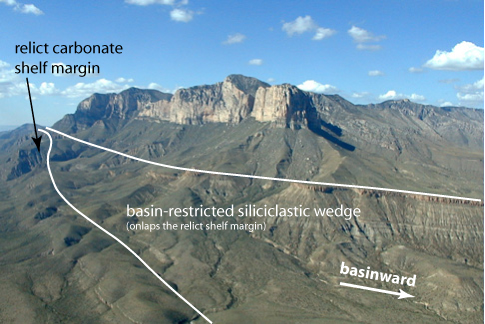

I did not take this photograph below…it was taken by my master’s degree adviser from a helicopter.

This is where I am right now…well, right now I’m on my way here. This is the western escarpment of the Guadalupe Mountains in west Texas. The prominent light-colored cliff-forming rocks at the top is the famous Permian Capitan Formation. In fact, the highest peak there is called Guadalupe Peak and is the highest point in Texas (8,749 ft). The Capitan is a fossiliferous limestone reef succession. The regional dip of the strata is to the east (to the right on the photo); a few tens of km away this limestone package dives into the subsurface and is the rocks in which Carlsbad Caverns is located. If you have the chance to go, you should do it.

The rocks underlying the Capitan Reef, although not as photogenic and striking, are incredibly interesting geologically. This escarpment is essentially a cross section of an exhumed Permian shelf margin. It’s difficult to explain in words, so I make a few annotations on the photo below showing what I’m talking about.

We are on a student-run field trip right now and one of the days is to hike halfway up in the area where the basin-restricted wedge pinches out against the underlying shelf margin.

You can find out more details about the geology and fantastic stratigraphic relationships exposed here, here, or here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Media blowing an opportunity to educate the public about subduction zones

As you all know, there has been a flurry of seismic activity offshore of Sumatra the past few days, and with it a flurry of media reports. The reporting about basic stats such as location, time, magnitude, effects on lives and property, and fears of possible tsunamis is pretty good. If you are looking for this essential information about the event, you can typically find it in the mainstream media reports.

But, they are missing an opportunity to educate their readers about the geologic conditions that lead to the seismic activity. Perhaps I’m biased, but I don’t think it is too detailed to include fundamental plate tectonic concepts in this kind of reporting. If this information is included every time these events occur, then the general public will get accustomed to it over time. It will become conventional wisdom. Meteorologists discuss low and high pressure cells every day, shouldn’t we also discuss convergent, divergent, and transform plate boundaries?

I could envision very simplified (but still accurate) block diagrams or cross sections showing the subduction zone. Instead of showing just a political map (like the NYT article here), why not show a topographic-bathymetric map? This CNN.com report does mention that this region is a subduction zone, but I think we can do better. If the general public sees the same diagrams and visual explanations each time a major event occurs, then their knowledge and understanding would improve over time.

I’m being a little nit-picky…overall, many of the news agencies do a decent job of reporting the necessary information. But, there is definitely room for improvement. Photographs of collapsed buildings do play a role, but those images ought to be connected with images that represent the fundamental understanding of what causes these events.

This quote from the CNN report demonstrates how experience can improve knowledge and thus preparedness.

The relatively light loss of life can be attributed to national and provincial governments being battle-tested by a string of powerful earthquakes over the last three years, Bakrie said.

I think we could also do this with the fundamental understanding.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Submarine fans during a highstand in sea level

![]() As I mentioned a few weeks back, I am a co-author on a paper in the September 2007 edition of Geology. The first author, a collaborator of mine, does not have a blog (he’s too busy publishing papers!), so I figured I would write a post about the paper here on Clastic Detritus.

As I mentioned a few weeks back, I am a co-author on a paper in the September 2007 edition of Geology. The first author, a collaborator of mine, does not have a blog (he’s too busy publishing papers!), so I figured I would write a post about the paper here on Clastic Detritus.

The title is: Highstand fans in the California Borderland: The overlooked deep-water depositional system

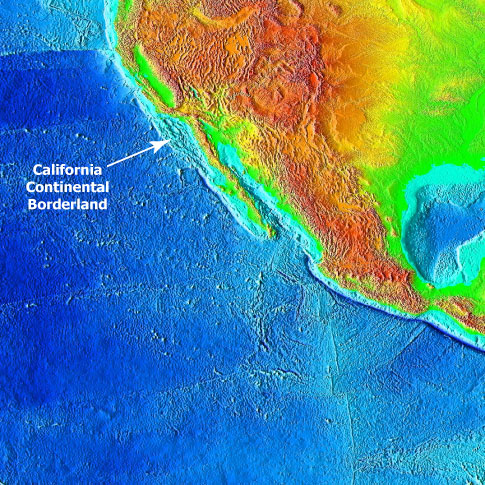

I’ll get into what highstand fans are in a moment. First, what is the California Borderland? The NOAA topography-bathymetry map below shows a continental-scale view of the southwestern part of North America. The California Continental Borderland is that rhomb-shaped area offshore and south of the big bend in the San Andreas transform margin. It extends southward offshore of Baja California but the offshore part narrows considerably.

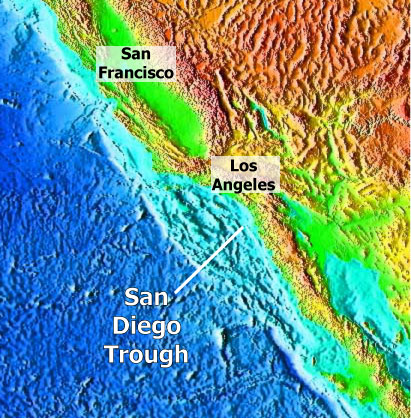

The next image (below) zooms in a bit and nicely shows the pockmarked nature of the Borderland (area in the lighter blue color). The crust in this area experienced some extension (stretching) ~10-15 million years ago (give or take) producing deep basins bounded by normal faults. In the last few million years, compression related to the evolving San Andreas system reactivated some of these normal faults into reverse faults and thrust faults. So now, these deep basins are bounded by some uplifting submarine ridges, some of which pop out of the ocean as the Channel Islands. To see a perspective view of the Borderland, check out this post from several months ago. We have been studying the basins directly adjacent to the present coastline and the sediments that fill them. The Highstand Fans paper focuses on the systems in the San Diego Trough.

Okay…that is a brief background on the setting of the Borderland region. If you want to learn more about the San Andreas Fault system and see more diagrams showing exactly where it goes, check out this USGS website.

So, the whole point of this paper is to highlight that submarine fans do indeed form and grow during highstands of sea level. Traditional sequence stratigraphic models typically show that significant sediment bypass from onshore to way offshore, in the deep-marine realm, occurs when sea level is low (called “lowstand”).

Below are some idealized figures showing the difference between lowstand and highstand within the context of conventional sequence stratigraphic models. I annotated these images, which are from the fantastic Univ of South Carolina sequence stratigraphy website.

As I said above, when sea level is low, coarse-grained sediment bypasses the exposed shelf and accumulates in deep-water as a submarine fan. During highstands of sea level, the coastal plain and shelf is accumulating sediment and the deep basin is starved resulting in no submarine fan growth.

The most important thing to remember is that these conceptual models were developed from data along passive margins (e.g., east coast of North America, west coast of Africa, etc.) where large sedimentary systems build out basinward (like the Mississippi delta is doing). In that context, the highstand vs. lowstand model does indeed work. There are certainly some exceptions, but by-and-large, this is not a horrible rule of thumb for passive continental margins.

For tectonically active continental margins, however, we have a completely different story. We, of course, are not the first to point this out. Several previous studies have documented the occurrence of turbidite deposition during the current highstand. With this paper, we wanted to go beyond documenting the presence of a system and dig a little deeper by analyzing volumes of sediment and rates of accumulation of both highstand and lowstand systems in one area.

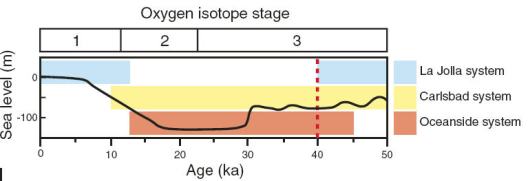

Okay, so I’m going to attempt to lay all this out without a lot of jargon and extraneous information. There are three different submarine fan systems. The figure below shows the activity of these systems against the sea-level curve (black line) and oxygen isotope stages since 50 ka (50,000 years ago). When the black curve is low, sea level is low. Note that La Jolla system (light blue) is active during relative highstands whereas the other two are active during lowstands.

Using a tight grid of seismic-reflection profiles we (i.e., the first author) painstakingly correlated and mapped out the distribution of the three submarine fan systems. Radiocarbon ages from boreholes provide the constraint on timing and help confirm correlations. After all that, we calculated the sediment volumes and associated accumulation rates. We found that the highstand system (the light blue above) accumulated more sediment in a shorter time than the other two systems combined since 40 ka.

It gets even more interesting (to sed dorks like me, anyway) when you look at how these submarine fan systems are fed coarse-grained sediment. There are no large rivers dumping directly into the submarine canyons that feed the submarine fans. They get their sand from the beach. At present, La Jolla submarine canyon receives sand directly from the beach…the canyon head goes nearly right up to the beach. See this post from a while back showing a bathymetric image of La Jolla submarine canyon.

In this area, there is a north-to-south longshore drift (called a littoral cell) that transports sand along the beach. When a submarine canyon intersects the littoral cell…the beach sand has the potential to be carried down into the submarine canyon as a turbidity current and then deposited way offshore on a submarine fan. The image below from the paper shows the difference in littoral cell/submarine canyon activity during highstand vs. lowstand periods.

The left part of the figure shows that during the last lowstand (~20,000 years ago), the coastline was out at the current continental shelf edge. Numerous submarine canyons and gullies head at the shelf edge and were able to intersect sand from numerous littoral cells. During the more recent highstand in sea level, the shelf was flooded pushing the coastline back leaving the shelf-edge canyon heads stranded. In this situation, the littoral cell sand just keeps on going south until it is intersected by the La Jolla submarine canyon. So, all those smaller littoral cells are combined into one (called the Oceanside littoral cell) during the highstand. This results in one larger submarine fan instead of numerous smaller submarine fans.

So, in this situation not only does submarine growth occur during a highstand in sea level, the fan is more voluminous and accumulates sediment at a faster rate. Does this rock the foundation of sequence stratigraphy to its very core? Not really. But, as we point out in the paper, the application of the lowstand-only models is what is widespread. The sequence strat models themselves are not the issue…just the application of them to any and every turbidite system on the planet. The fact that tectonically active margins have relatively narrow continental shelves (10s of km) compared to passive margins (100s of km) is the fundamental difference.

An additional aspect of this kind of research relates to trying to quantify the volumes and rates of sediment transfer from onshore to offshore. Tectonic geomorphologists are busy calculating rates of erosion, denudation, and uplift in mountainous onshore areas (the source of sediment). The timing and distribution of sediment accumulation in the “sink” offshore needs to be integrated with the onshore work. Hopefully, getting at all these various rates (accumulation, erosion, denudation, uplift, subsidence, etc.) will lead us to a better understanding of the dynamics of continental margins.

–

Link to full text of pdf here (w/ subscription).

A Comment and Reply published in Geology came out in April 2008, see this post.

–

Covault, J., Normark, W., Romans, B., & Graham, S. (2007). Highstand fans in the California borderland: The overlooked deep-water depositional systems Geology, 35 (9) DOI: 10.1130/G23800A.1

A geo-bio theme for next carnival?

Kevin Z of The Other 95% made a comment in The Accretionary Wedge #1 proposing a interdisciplinary theme for the next carnival. I’m posting it here just in case you didn’t see it in the comments.

This carnival was a great idea. I like how the posts reflected a theme as well. I’d like to propose another theme that I would be willing to host at my blog The Other 95%. As a biologist with a bunch of geology behind him, I am always fascinated by the interplay of geology and biology. So I would like to propose the theme: At the Melting Point – The Intersection of Rock and Life. The theme can be broadly applied. Any takers?

I am leaving later this week for a 2-week trip and will be away from the internets the whole time. So, i’m gonna pass on this particular proposal…but, it sounds pretty cool. Feel free to use the comment thread in TAW#1 post to discuss.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Misleading science headline of the day

A couple weeks ago, Kim used the same post title I am above regarding an article about subsidence of the Mississippi River.

Today, I’m going to pick on ScienceDaily for this one:

Marine Team Finds Surprising Evidence Supporting A Great Biblical Flood

It’s an article about ongoing work in the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions where evidence of ancient civilizations and their fates are being integrated with more and better environmental information. What was the climate like? Where was sea level? Etc. And the article actually talks about the vessel and the program in general more so than any specific results.

This headline is misleading on many accounts. Why is the evidence “surprising”? What does ‘biblical’ mean? Ideas and evidence about the breaching of the Bosphorus and flooding of the Black Sea have been around for some time. The one paragraph in the article that even mentions this (about halfway through) seems to me more like additional confirmation…not ‘surprising evidence’.

I am so frustrated with what is clearly some editor’s decision to change the title to something ‘punchier’ and ‘sexier’ to attract readers. Not only is it misleading to what the article is about, it is misleading regarding the state of the science of timing and nature of the significant environmental and physiographic changes our planet has seen since the last glacial maximum (~18,000 years ago).

I urge everyone to go out there and nit-pick and complain about other science news articles. If we don’t, who will? Besides, it’s a nice release if you’re frustrated with it.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~