Sea-Floor Sunday #10: Puerto Rico Trench

UPDATE: Also see this post from December 2009 of higher-resolution bathymetric images from the same region.

–

I guess I’m feeling subductive this week (see Friday Field Foto #40). The bathymetric image for today is a perspective view (looking west) of the North American and Caribbean plate boundary focused on the northeast part of the Caribbean Plate.

The image below is from the Caribbean earthquake and tsunami hazards studies page of the USGS’s Woods Hole Science Center.

The Puerto Rico Trench reaches water depths greater than 8 km making it the deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean (the Marianas Trench gets to 11 km in case you’re wondering). The North American Plate is subducting underneath Caribbean Plate. In the view above, the main subduction zone where the plate motions are more orthogonal are further south. This view is where the arc starts to curve around to the west.

This map below (found here) shows a simplified map of the region and the primary tectonic boundaries. The bathymetric image above is the area where it says Puerto Rico Trench in the northeastern part of the Caribbean Plate.

A few years ago I went to the conference ‘Backbone of the Americas’ in Mendoza, Argentina. The conference was focused on the tectonics of both North and South America. One of the best talks I saw was by Pindell about the Caribbean area. It is quite a messy area tectonically with many aspects not fully agreed upon (which is fun!).

To find out more, this page is GoogleScholar with Pindell as author. There’s tons of stuff there to check out.

~

See all Sea Floor Sunday posts here.

Friday Field Foto #40: Chert from the Franciscan subduction complex

It’s been a quiet week on Clastic Detritus … we went through a move earlier this week to be a little closer to my new job. We are still in the San Francisco Bay Area, not too far from where we used to live. We’ve spent the last week thinking about how we are going to get to our favorite Bay Area spots. So, for today’s Friday Field Foto I’m going to show you some of my favorite Bay Area rocks.

These radiolarian cherts are beautifully exposed in the Marin Headlands area just over the Golden Gate Bridge north of San Francisco. Most people drive up there and stop along the pull-outs to gaze upon the bridge and the city skyline. Others (i.e., those of you reading this blog) take a look at the scenery and then turn around to look at these brick red and commonly spectacularly folded cherts. [This is a nice, big image…click on it for closer view].

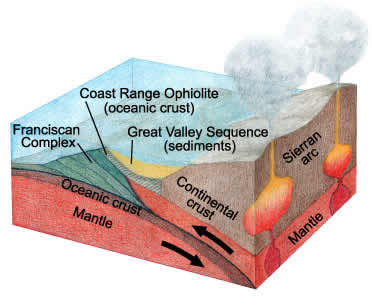

The Marin Headlands are part of the Coast Ranges along the western edge of central and northern California (north of where the San Andreas Fault goes offshore) is made up of the Franciscan Subduction Complex. Today, the southern limit of subduction is the Mendocino Triple Junction. This triple junction (and the transform margin) has migrated north over time, however. Once upon a time, subduction was occurring all along central California (producing the Sierra Nevada arc which is so beautifully exhumed now).

Here is a part of the California geologic map with some of my scribblings on it. The boundaries I’ve drawn for the Franciscan Complex are not super precise … but for the purposes of this post it will do.

A subduction complex, by its very nature, is a complete mess. Essentially, this is material that has been scraped off the subducting plate and piled up against the continental margin. What’s fantastic about California is that the San Andreas transform has preserved the elements of the Mesozoic convergent margin for us to see. In the map above, you can easily see the three main elements of this system: (1) subduction complex, (2) forearc basin (Great Valley), and (3) magmatic arc (Sierra Nevada).

This schematic cartoon portrays this system in cross section [image source here].

There are some interesting details regarding these cherts and their actual origin that I’ll post when I have more time. For now, I wanted to put them in this bigger plate tectonic context.

If you are ever in San Francisco, make sure to take a trip to the Marin Headlands and check out these fantastic messed up cherts. Oh, and there are some decent views of one of the best cities in the world too.

Happy Friday!

~

Check out this Friday Field Foto of some pillow basalts exposed on the Marin Headlands that are also part of this subduction complex.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Will science reporters ever get it?

I saw a link to this LiveScience report over at Southern Exposure just now.

Now, I’m not going to argue that human civilization hasn’t significantly changed the planet. We have. And I’m not going to argue that we shouldn’t call the current time something new to reflect that. We probably should.

What miffs me is the language. Check out the title of the article:

Humans Force Earth into New Geologic Epoch

WTF? It’s as if the new epoch was coming sometime in the future, but we made it come quicker. WE MAKE UP THE TIME PERIODS PEOPLE!!! We decide when the boundaries are. They don’t frickin’ exist without us!

Let’s look at the first statement in the article:

Humans have altered Earth so much that scientists say a new epoch in the planet’s geologic history has begun.

Maybe one can say I’m being nit-picky about semantics, but don’t you see what’s wrong with this? “…scientists say a new epoch…has begun”. Wrong. Scientists are saying we ought to CALL it a new one to reflect these changes. It’s as if the time periods exist somehow and we discovered them, their boundaries, and all their Anglo-Saxon (with some Russian, French, and others) names.

I blogged about this some months ago. All too often, I hear something like “When the Cretaceous period came to a close, the dinosaurs died out”. Wrong. The Cretaceous ends there BECAUSE the dinosaurs died out. We made up these time periods based on that. Argh.

Science reporters, students, general public … it’s time to stop the madness. Call me a jerk, but it’s time to get your heads out of your a@#es and understand this. It’s everybody’s fault.

Whew…I feel better.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A little quiet around here

My life is all about boxes right now. We are moving to a new place and tomorrow is the big day. It is only 15 miles away, which makes it seem even more ridiculous to pack up everything so neatly only to rip open the boxes an hour later. Such is life.

In the meantime, check out some happenin’s on the geoblogosphere:

- I’ve been enjoying (and getting quite jealous of) Geotripper’s airline chronicles photograph series

- Tell Callan how those cool ice balls form

- Alessia continues to post from Antarctica … these are great, short snapshots of life as an seismology researcher in a harsh environment

- Ole wonders if this theory has any legs

- Ontario-geofish talks about rock mechanics

- Lab Lemming decided what the February 2008 Accretionary Wedge topic will be

- Where on (Google)Earth #104 is up at The Lost Geologist

- Join the discussion about what happened to the Tertiary

We don’t have our internet situation quite figured out yet in the new place … hopefully I won’t be without for too long.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Friday Field Foto #39: Prograding deltaic deposits

This week’s photo is from the Cretaceous of Utah. This is a unit called the Ferron Sandstone Member (Turonian), which is part of the Mancos Formation.

This photo is taken from Interstate 70 on the western limb of the San Rafael Swell (where the Ferron is exposed beautifully for several 10s of km).

It is hard to get a sense of scale on that photo … but the reddish-brown fallen block on the right side on the talus slope is probably the size of a bus (roughly).

Without going into too much detail, essentially you are looking at prograding delta-front deposits in the lower cliffs (notice the upward-coarsening and upward-bed thickening pattern) with fluvial channel deposits (the more buff-colored sandstone) overlying it.

Overall, the Ferron represents a clastic wedge that prograded into the Cretaceous Seaway. These strata are older than the more commonly visited outcrops of the Book Cliffs I’ve talked about before (here and here).

I visited the Ferron a few times when I was working on my master’s in Colorado. When I find a little time, I’ll put together a more comprehensive post…these are cool rocks!

Happy Friday!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Ideas for next The Accretionary Wedge

Although the excitement of The Wedge #5 is still reverberating throughout the geoblogosphere, it’s never too early to start thinking about next month’s installment.

Head over to this post at the TAW archive site to discuss ideas and who’s hosting.

UPDATE: Lab Lemming is going to host and picked a topic … check it out here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Geologic Misconceptions: “Layer-cake” stratigraphy

This post is part of the fifth installment of the geoscience blog carnival, The Accretionary Wedge. The topic is ‘geologic misconceptions’ and it is also National Pie Day. Instead of pie, I discuss cake … a very messy, uneven cake. Head on over to Green Gabbro for info and links to all the posts for TAW #5.

~

I don’t care if the sedimentary layers in this image “look” flat…they’re not.

Okay … maybe they are essentially “flat” over a few or even several 10s to 100s of kilometers. But … as one who studies strata, one of my pet-peeves is the portrayal of sedimentary successions as perfectly flat layers.

It is more appropriate to think of sedimentary layers as sedimentary bodies. No sedimentary layer goes on forever … they eventually pinch out, get cut out, or gradually change into a different type of sedimentary rock. As a result, these bodies have a shape to them … they are not rectangles. Nearly all sedimentary bodies, when viewed in a 2-D cross section, are some sort of wedge-shaped body. Bailey (1998) called these bodies “lenticles”, that is, they have a lenticular shape. The geometry might not be visible unless you impose a great deal of vertical exaggeration (as stratigraphers often do with cross sections) but it is there nonetheless.

Why does this bother me? Or, to put it another way, why is this important?

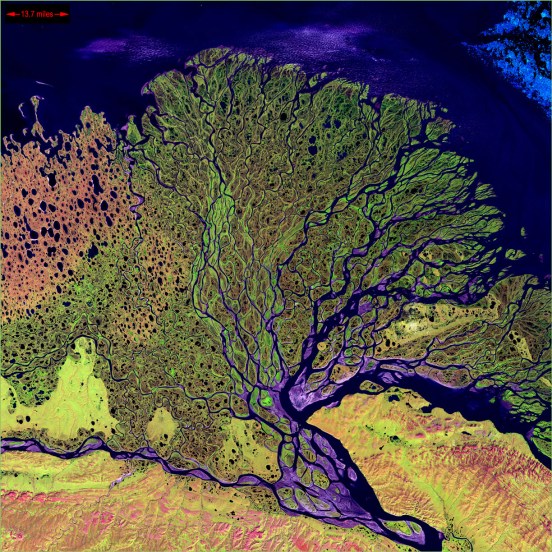

The “layer-cake” view of stratigraphy bothers me because it does not appreciate (1) complex patterns of deposition/erosion or (2) complex patterns of preservation. A snapshot of a depositional system (i.e., some place where there is net accumulation of sediment) looks more like this:

That’s the Lena Delta in Siberia from GoogleEarth … click on it for a nice, hi-res version.

In most cases, however, we do not see a fully-preserved delta in the rock record. The processes of long-term preservation creates a body of sediment/rock that is typically an amalgam of numerous elements of the system over a long period of time. These processes can, in some cases, “smooth” out some complexities but they also introduce some of their own.

Most geologists who don’t specialize in stratigraphy know what I’m talking about. If you do a lot of field geology and have done some mapping, you have, at one time or another, had to deal with units that have significant thickness changes or the study area. In other cases, you may have been able to treat the sedimentary layers as having essentially constant thickness across the mapped area (e.g., some epeiric sea carbonate rocks do indeed go on for 100s of km with little thickness change).

But, the point of bringing this up is not so much for geologists, but for everyone else. Of course, the term stratigraphy itself is rooted with the word for “layer”. I’m not going to get too nit-picky…that’s fine if we call them layers. But, the next time (and every time after that) that you are looking at a sedimentary “layer” remember that what you are looking at is actually a 3-D body with a complex shape and even more complex history.

–

UPDATE: check out the post by Hindered Settling about misconceptions that arise from 2-D vs. 3-D representations.

Geobloggers: submit posts to Research Blogging website

The folks from bpr3.org have launched their new site, called ResearchBlogging.org, which collects all the posts our there in science blog land that have been tagged as “blogging on peer-reviewed research”. You know, that little icon with the green checkmark people have been using the last few months.

If you’re not sure what I’m talking about, check this site out and then come back and read this.

I signed up and it was a relatively straightforward process to get my latest post about peer-reviewed research up there. The researchblogging.org site also automatically creates a citation and link to the paper you are blogging about. You simply enter the DOI (or other info if you don’t have that) and it shows up there. I think this is great. Firstly, the reader can click on that right away to get the paper…that’s just plain and simple convenience. Secondly, it keeps posts out that aren’t really about a real paper. Most science blogs (including me) have other posts not really about any particular research paper. This is a great filter. I simply don’t have the time to sift through the hundreds or thousands of science-related posts per day to find good comments about a recent study, especially if it’s out of my field.

In addition, I like the layout and look of the researchblogging.org site … it is very simple and effective. Here is a screenshot of what it looks like.

Like a regular feed, it has the post title and a snippet of text. But, then it has the citation and a link for the paper you are discussing.

What I’m getting at here is … sign up!!! The geosciences will be weak and under-represented unless we can get a posse together to put together quality posts about research topics.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sea-Floor Sunday #9: Continental slope near Fraser Island, Australia

![]() This week I decided to combine a sea floor image with a post about a paper that came out in Geology this month about everybody’s favorite topic — sediment transfer to the deep sea! The paper is called Highstand transport of coastal sand to the deep ocean: A case study from Fraser Island, Australia by Ron Boyd and coauthors mostly from University of Newcastle. Click here to go to the Geology site where you can view the full text or download the PDF (subscription required).

This week I decided to combine a sea floor image with a post about a paper that came out in Geology this month about everybody’s favorite topic — sediment transfer to the deep sea! The paper is called Highstand transport of coastal sand to the deep ocean: A case study from Fraser Island, Australia by Ron Boyd and coauthors mostly from University of Newcastle. Click here to go to the Geology site where you can view the full text or download the PDF (subscription required).

The image below is a quick snapshot from GoogleEarth just for some context of the study area. Fraser Island is the largest and northernmost of a series of sand islands created from south-to-north longshore transport. As Boyd et al. point out, at 1500 km, this is the longest littoral cell transport system in the world.

The next image below (their Fig. 1) is a perspective image of the continental margin now looking toward the southwest. Fraser Island is at the top-center of the image. Note the arrows showing transport direction of the littoral cell to the north. Click on it to see a bigger and better-resolved image.

Fraser Island and its subaqueous extension, called Breaksea Spit, extend out away from the Australian margin as it starts to curve toward the west. This is where the sand transport aspect of the system is very interesting. The constructional Fraser Island-Breaksea Spit has built out to the edge of the continental shelf. When sand is reworked and transported along the system it intersects the shelf edge thus transporting the sand into the deep sea (called ‘intersection zone’ in their figure above). Note the erosional conduits cut into the continental slope just below the intersection zone.

Last September I posted about a paper of a colleague of mine and others in our research group discussing a somewhat similar system in southern California. Details of the Fraser Island and southern CA transport systems are quite different, but, in a general sense, it is worthwhile to compare them.

The most important aspect to compare is how coarse-grained sediment along the shoreline (where wave action in shallow water is strong enough to transport sand) gets to the steep gradients of the continental slope (where sediment gravity flow processes dominate). In other words, how is the shoreline connected to the slope? In the southern CA system, the shoreline is connected to the continental slope because a submarine canyon has cut back across the relatively narrow shelf. In the Fraser Island system, a depositional system has built out to the shelf edge.

These systems are important to characterize because we are always trying to infer such transport pathways when we are investigating deep-marine sandstones in the rock record. Being able to draw upon examples from modern systems emphasizes the interactions of fundamental controls like tectonic setting and sea-level stands.

Another important aspect of the characterization of these sediment pathways has implications to a broader understanding of exactly how other materials (pollutants, terrestrial carbon, etc.) make their way to the ocean.

~

Boyd, R., Ruming, K., Goodwin, I., Sandstrom, M., Schröder-Adams, C. (2008). Highstand transport of coastal sand to the deep ocean: A case study from Fraser Island, southeast Australia. Geology, 36(1), 15. DOI: 10.1130/G24211A.1

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Science blogger vs. blogging scientist

Every once in a while I post about some misleading or erroneous science reporting (or at least what I perceive to be misleading) . If I’m in a particular mood, the post becomes more of a rant than a well-written essay. This is the freedom of blogging, right? A science book author and blogger took exception to my admittedly sloppy rant about sloppy use of words…fair enough.

Additionally,

YamiMaria recently touched on why she won’t be using her blog for semi-serious “reporting” of peer-reviewed research (her and some commenters there have some good points). Ole chimed in as well about why he blogs about geology.This made me wonder about the constantly-growing group of blogs we tend to group into “science blogs”. What are science blogs?

A wise person once said there are two kinds of people in the world; those that divide the world into two kinds of people and those that don’t. For the sake of argument, it seems to me there are two kinds of science-related blogs:

(1) blogs about science

(2) blogs by scientists

Let’s call them science blogger (Type I) and blogging scientist (Type II). Some of Type I blogs are by authors/writers/journalists who may have experience and a degree in science but are now within the general field of science communication. Some Type II blogs are by practicing researchers/students/faculty and cover a broad range of topics, most related to science in one way or another, but also including a few off-topic or personal posts as well.

These types are fluid. That is, one blog can exhibit traits of either type from post to post. Some blogs switch back and forth a lot, some stick to one type or the other most of the time.

This is, of course, a grossly oversimplified classification of something that is more of a continuum (as always).

I tend to view my own blog (right or wrong) as a mix of both types. The last half of 2007 contained numerous posts about finishing my dissertation. Not so much about the content, but the general process and thoughts about it. But, I also attempt to write posts every once in a while that delve into a scientific topic, concept, or recent paper in more detail.

What about you? What kind of mix do you think you have? Or, is my oversimplified view so oversimplified that it’s not even worth discussing?

~

Note: Don’t read this post as if I think I’m the first to discuss this … obviously, this issue has been covered before. Probably many times. I simply do not have the time nor the energy to do that research. Searching and sifting through the myriad blog threads would take some serious effort. Feel free to leave links in the comments for any discussions or threads you think address this (probably better than I have).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~