Friday Field Foto #35: Pontificating in Bone Canyon

I typically don’t post photographs of myself…or of people, in general, for some reason. One reason might be that I have way more photographs of geologic features than I do of people. If people are in them, its usually for scale.

But, I couldn’t pass this one up. A colleague of mine gave this to me yesterday. Back in September we ran a field trip to west Texas and southern New Mexico to look at all the fantastic geology. I posted some photos from that trip before (see here).

I did my master’s work on the Permian turbidite deposits that are exposed in the Guadalupe and Delaware mountains. Although I had only been to this locale twice before on other field trips, I was the obvious choice to lead that day. It turned out that I remembered more of the details once we got there than I thought I would.

Here I am in Bone Canyon (Guadalupe Mts Nat’l Park) pointing out some of the features of an ancient submarine canyon. It’s great. You can go and see sandy turbidites lap up against a relict canyon wall and completely fill the canyon.

Way above, on the skyline, is the highest point in Texas, Guadalupe Peak.

–

See all Friday Field Fotos here

See all posts tagged with ‘west Texas’ here

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A pet peeve about the portrayal of geologic time…

This is quick, random, and a little ranty.

There was a program on PBS last night about early dinosaurs. It seemed a little dated (I don’t know, maybe from the late 80s/early 90s). I wasn’t really watching it…since we don’t have cable we end up watching a lot of PBS (it’s either that or Are You Smarter Than a 5th-Grader, which is a different rant for another time).

Anyway…I really dislike these statements (I’m paraphrasing):

And then the Permian period ended and gave way to the Triassic period. At the same time, a major extinction, a mass extinction occurred.

They make it sound like a coincidence. As if the Permian and Triassic periods somehow exist as fundamental divisions of time. Wrong. The Permian period ends because of the mass extinction. That’s how it’s defined!! I hear this all the time for the K-T as well on these, otherwise fairly enjoyable, popular science programs. It’s not ‘the dinosaurs became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous’ … it’s ‘the end of the Cretaceous is marked by a mass extinction, including dinosaurs’.

It’s not that hard.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rock and life: Trace fossils

I know it sounds lame to bring out this excuse (yet again) … but it’s the truth! I have to hand in my dissertation to my committee in less than a week and simply don’t have the time for a real post. But…I couldn’t bear not contributing to this edition of The Accretionary Wedge (#3), which is about the intersection of geology and biology…of rock and life. It’s being hosted at the blog The Other 95%, check it out here.

~

I’d like to live beneath the dirt

A tiny space to move and breathe

Is all that I would ever need

lyrics from “Dirt” by Phish

~

For the rock and life edition of TAW, I’m gonna show you some photographs I’ve taken from my own field research showcasing trace fossils.

Trace fossils are not body fossils; they are simply tracks and traces of organisms preserved in the rock record. Human footprints in sand or mud, if lithified and preserved, are trace fossils. Most of my research is about the sedimentological characteristics and processes/mechanics of deposition, but the traces are there. In some cases, trace fossils are extremely useful for paleoenvironmental reconstruction or other paleoecological considerations.

Remember, these are not body fossils. What we are looking at is evidence of behavior of the organism Were they burrowing to escape something? Were they grazing for food?

Alright…here we go. Most of these are from Cretaceous turbidites in Patagonia. The captions are below the photo. If you click on them, you’ll get a slightly bigger version.

This is a bedding-plane view (i.e., looking down on top of the bed). Note the nice cross-cutting relationships of these various traces.

This is now looking at the cross section of a sandstone bed. This is a near vertical sand-filled tube with some internal structure. Ichnologists (those who study trace fossils) have given names to the myriad types of traces. This one is called Ophiomorpha. In modern settings, very similar burrows are made by a type of shrimp.

Another sand-filled vertical tube.

Another bedding-plane view of criss-crossing and branching traces.

This is a big one! Another Ophiomorpha (the divisions on the staff are 10 cm).

This is a mud-matrix conglomerate deposit. The light-colored, discontinuous vertical streaks are sand-filled burrows. Note how some are curving around the pebbles and cobbles (whatever the little buggers were could not have burrowed through them).

This one (only one not from Patagonia; is from Mississippian of New Mexico) is a bedding-plane view of some very intricate and beautiful traces called Zoophycus. Ichno-geeks interpret these as representing grazing traces.

Finally…this one looks boring because it is so burrowed that you cannot distinguish individual traces. It’s completely bioturbated (what a great word). A high degree of bioturbation is typical of a shallow marine setting where there is plenty of oxygen and food making burrowing creatures very happy.

–

That’s it! Rock and life!

The archive website for The Accretionary Wedge is here … please go and use it as a place to discuss future ideas and to organize hosting.

Must. Finish. Dissertation.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

How old is the Earth’s youngest exhumed pluton?

I don’t have the answer to this…I’m actually posting this to get help from my geoscience blogging colleagues. Lab Lemming and/or Thermochronic, in particular, might have some good leads for me.

This is a question that I’ve been pondering this evening as I write up this last chapter on some detrital zircon data. We are looking at sedimentary rocks that were deposited in the Late Cretaceous (spanning from ~85 to 70 million years ago). The source area for this basin was an active continental arc. There’s a boatload of volcanic and volcaniclastic grains in the sandstones and we are finding zircons that are only slightly older than the suspected depositional age. Furthermore, we are finding populations of nearly concurrent zircons as we go up through the stratigraphy. That is, the next younger formation includes a population of zircons younger than the depositional age of the formation below it. This is a pattern that is being found in other arc-sourced detrital records as well.

One issue is that the biostratigraphic control is poor and we don’t have any ashes for absolute dating. The detritals are actually helping constrain the timing of deposition.

This made me wonder … just how quickly can a zircon go from crystallization in an arc pluton to being a grain of sediment? Or, put another way, what is the age of the Earth’s youngest exhumed pluton? This seems like one of those things that other geologists probably know off the top of their head. Along those lines, how common is it for zircons that crystallize at depth to be transported to the surface via volcanism?

Any references, resources, papers, etc. appreciated.

–

UPDATE: Ron found a paper discussing a ~1 million year-old exhumed pluton in Japan (see full citation in comments below). This is the winner so far.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Tactics for effective dissertation writing

If you clicked on that post title from somewhere else and thought you might be getting a thoughtful and comprehensive post filled with tips and advice about effective writing…well, sorry…

If you clicked on that post title from somewhere else and thought you might be getting a thoughtful and comprehensive post filled with tips and advice about effective writing…well, sorry…

I am getting so close to the deadline of having to hand my dissertation into my committee. Close enought that I don’t even want to mention it. I am finishing up the Discussion section of the only remaining chapter. The other sections have been or are in the process of being reviewed by my coauthors. The figures and tables are done (except for a nifty summary figure that is still in my head).

So…the Discussion section. You know, this is the fun part, right? This is where you can leave all that anal-retentivity behind and freely postulate outrageous things! Well, not quite. But, it is certainly more interesting to write about implications your results may have than writing the bland (yet extremely important) descriptions of rocks, plots, cross sections, maps, and so on.

Being more interesting, however, is typically more challenging. I find myself sitting looking at the dang Word document staring right back at me as if to say “c’mon…do it…whaddya got?”

Here are a few of my tactics for effective writing:

- Jump around wildly from one sub-section to another with no apparent plan (see a previous post of mine about that method here).

- When you can’t think of anything to write but feel way too guilty to check your email or … gasp … post on your blog, futz around with your Acknowledgements, figure captions, or other such thing. Then it feels like your still working even though you’ve accomplished nothing.

- Look at the calendar again just to make sure you correctly counted how many days until the deadline. Depending on your emotional state (and caffeine level) this can lead to semi-severe panic, or it can lead to a moment of knodding your head and saying to yourself “this is easy, no problem, I’m so on top of this” … (it doesn’t matter if you don’t believe that, it’s all about survival now).

- Finally, at this point in the game, the deadline is so close that I simply cannot be separated from my computer. It is actually fused with my lap now. If a good idea or way to phrase something pops into my head, I need to be with the Word document ready to record it. If that window of opportunity shuts…that’s it. Gone.

These are just a few…i’m sure you all have your own tactics for effective writing. Feel free to educate me.

–

[image above from here]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sea-Floor Sunday #3: Gulf of Mexico continental slope

This blog has moved to Wired Science (as of Sept 14, 2010)

URL: http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/clasticdetritus/

RSS: http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/category/clastic-detritus/feed

–

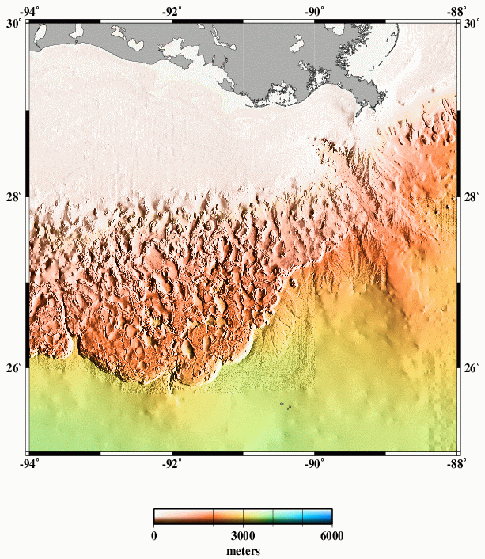

The continental slope in the northern Gulf of Mexico has a very distinct appearance. Note the pock-marked nature in the water depths colored red in this bathymetric image below. The coastal area at the northern end of the image is the Mississippi delta of Louisiana.

The transition from the pock-marked slope to the smoother and lower-gradient abyssal plain (yellowish colors in image above) is a rather abrupt escarpment with nearly 1,000 m of relief.

Here’s another image of the GoM continental slope from a great Geology paper from over 10 years ago now by Pratson and Haxby (link to paper here). This is a perspective view looking towards the east. The black area in the upper left is the continental shelf.

The escarpment I pointed out above is clearly visible in this perspective image. Note the arcuate shape of the trend of this escarpment (called the Sigsbee Escarpment). If it reminds you of a thrust-front, that’s because it is!

The morphology of the GoM continental slope is dominated by salt tectonics. Jurassic evaporites have evacuated causing some areas to sink (the pocks, or “mini-basins”). That evacuation is balanced by salt diapirsm in other areas. Overall, the entire slope is affected by gravity and slowly moving towards the deeper part of the basin. The Sigsbee escarpment is the compressional front of that large-scale movement. In detail, each mini-basin is extraordinarily complex showing fascinating relationships between turbidite sedimentation and salt movement. A feedback is set up such that turbidites are deposited in the lowest parts (that’s what they do), which causes more underlying salt to evacuate, which in turn makes the basin subside, which maintains that spot being the lowest. Some mini-basins have 20,000 feet of Quaternary sediment in them!

There’s tons of information out there regarding the Gulf of Mexico. If you’re interested in more, you won’t have much trouble finding cool stuff.

–

Check out this page (a professor at Colorado School of Mines) for more about salt tectonics, in general.

Top image from here.

See all Sea-Floor Sunday posts here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Weekend geoscience blog roundup

Because I can’t think of anything interesting to post about, here’s a real quick list of some other goings-on in the geoblogosphere this weekend.

- I had been going through some Apparent Dip withdrawal … but, Thermochronic is back with a great post about everything you wanted to know regarding the mineral separation process but were afraid to ask. If you’ve ever done it, you’ll like the post. If you haven’t, but will in the future, you should read it.

- Another geoblogger I thought had fallen off the face of the planet has also resurfaced. Check out the post over at Southern Exposure about a casual conversation with an optometrist about energy prices.

- A relatively new geoscience blog (at least new to me) is Rising to the Occasion, and has a great post about a rather odd e-mail exchange with a senior colleague.

- Yami is making me envious with some fun quantitative self-analysis of the blog Green Gabbro.

- Chris has a great little piece up at Naturejobs.com about who does his grunt work in the lab.

- The Lab Lemming tells us what he does when not lounging.

- Finally…Where on (Google)Earth? #70 is still unsolved, up at Ron’s blog, and it looks like he’s willing to offer hints.

I guess that’s it…i’m sure I missed something. I need to go back to writing about what these dang rare earth element plots mean for Patagonian tectonic evolution.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Friday Field Foto #34: Austral parakeets

More correctly, today is a Friday Field Video.

We have come across various interesting wildlife during our fieldwork in southern Chile (e.g., pygmy owl, guanaco, ibis). One of the more interesting, and seemingly out-of-place, creatures we happen upon are Austral parakeets. They are bright green, travel in large flocks, and make a lot of noise.

I shot this little video (30 sec) on my digital camera in March 2006. It was very early in the morning at our campsite and several parakeets took residence in a tree near our tents and proceeded to squawk for a good 30 minutes. The lighting is poor so you can’t see their brilliant colors, but you can see their silhouettes against the sky, and you can definitely hear the racket they make. An effective alarm clock.

Our tents are tucked underneath the trees toward the end of the video. And the rocks that we are studying here are up the hill to the right (not shown in video), and look like this once you hike up the mountain a bit.

—

See all Friday Field Foto posts here.

Check out my Patagonia Flickr page.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Can we just break the record already

We are starting to hear more and more reports about the rising price of oil. The screenshot at right is the price as of midday on Friday, November 9th, 2007.

We are starting to hear more and more reports about the rising price of oil. The screenshot at right is the price as of midday on Friday, November 9th, 2007.

There are a few reasons I can think of for why this is getting attention:

- it’s close to a nice, round number ($100)

- it’s close to, or already has surpassed, the all-time record*

- it’s something that everyone should be aware of

I would argue that the increase in reporting is much more about the first two bullet points. The media is responding to what the general public enjoys … people love round numbers, they go crazy over them (e.g., Y2K); and people love when records are about to be broken (e.g., Barry Bonds homeruns, Olympics, etc.).

In reality, however, we should be aware and rationally concerned about the rising price of oil regardless of round numbers and records. I’ve posted about this topic briefly before and have said that I am in the camp that thinks elevated prices might be good. That is, if the price of gasoline (petrol for my UK readers) is relatively high, perhaps people will start to think about our collective consumption of the important resource. But…if it goes too high too fast, this will be bad for obvious reasons.

Because I have training in petroleum geology and have some experience in the industry, I often get questions from family members or friends asking: “So, why is the price of gasoline so high?”.

To that, I usually respond: “Because you keep buying it”

—-

*It depends on which analysis you look to for the exact amount of the previous record adjusted for inflation. Some analyses say we’ve past it already; the highest of the various prices is $101.70. I’ll leave it to the economists to split hairs on how to figure this out.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~