Sand: The Neverending Story — a book review

The post below is my review and the first of two posts devoted to the book ‘Sand: The Neverending Story’ by Michael Welland^. The second post is a Q&A between me and Michael combined with an open Q&A in the comment thread for you to ask questions.

–

Pick up a single grain from the beach, look at it through a magnifying glass, and you have embarked on a journey taken by poets, artists, and philosophers — not to mention geologists.

–

I have to admit that when I found out there was a popular science book devoted to sand I got really excited. Not only am I geologist, but I am a sedimentary geologist … and not only am I a sedimentary geologist, but I specialize in clastic sediments — a lot of which is sand. So, perhaps it’s not a big surprise that I’m a fan of book all about sand. But, at the same time, because I’m a sand-lover (or an ‘arenophile’ as Welland calls us) I read this book not only for the enjoyment of the narrative but also for additional insights and specific facts about my field of study.

I have to admit that when I found out there was a popular science book devoted to sand I got really excited. Not only am I geologist, but I am a sedimentary geologist … and not only am I a sedimentary geologist, but I specialize in clastic sediments — a lot of which is sand. So, perhaps it’s not a big surprise that I’m a fan of book all about sand. But, at the same time, because I’m a sand-lover (or an ‘arenophile’ as Welland calls us) I read this book not only for the enjoyment of the narrative but also for additional insights and specific facts about my field of study.

However, this book is not just for the specialist. The subtitle for the edition I have is ‘The Neverending Story’* and the clever narrative that Welland employs throughout much of the book is the journey a grain of sand takes from birth (weathering and liberation of sand-sized particles from rock) through transport, deposition and burial, and, if the geologic situation is right, lithification of those grains into sandstone, and potentially the breakdown of that sandstone back to sand again.

… sand is one of our planet’s most ubiquitous and fundamental materials and is both a medium and a tool for nature’s gigantic and ever-changing sculptures.

This narrative is woven into a book that’s filled with fascinating facts and stories about the role sand has played in both natural and human history. Thus, ‘Sand’ is a great read for anyone interested in the story of one of nature’s most important geologic agents.

Thankfully, Michael Welland, who is himself a geologist, addresses one of the misconceptions about sand in the first few pages of the book — that is, what makes sand sand is the size of the particle, not what it’s made out of.

Our sand grain, newly born, finds itself, together with a motley collection of other detritus, organic and inorganic, as part of a soil, the in situ accumulation from the physical, chemical, and biological processes at work in a particular place. The sand grain is anonymous, waiting for rain and wind to sweep it away on an endless journey, to demonstrate its durability while its weaker companions fall by the wayside. But it is called sand not because of what it is made of or its origins, but because of how big it is.

The first two chapters of ‘Sand’ introduce the basics of this material and discuss some important fundamentals related to the fascinating, and surprising, physics of granular materials (and not just transport but also how this material behaves when mixed, vibrated, dropped, and more).

‘Sand’ then returns the narrative of the journey a grain of sand takes with a series of chapters related to river transport, transport by wind, coastal processes, and finally, export of sand to the deep sea. There is enough fluid dynamics and details of particle transport within these sections to satisfy sedimentologists, yet it is also presented in such a way to be accessible to the non-specialist. In fact, if I were to ever teach a course in clastic sedimentology to novice geologists I would assign these sections of ‘Sand’ as required reading. Welland communicates many of the details within stories about pioneering sedimentologists, especially Ralph Bagnold, and how their research changed the science forever. To me, this is the mark of a successful popular science book — if I wanted straight-up sedimentology I could open a textbook — but, ‘Sand’ discusses these concepts within a story. In this case, a story about nature interwoven with stories about the people who study nature.

I also enjoy Welland’s writing style — some passages almost approach a rhythmic, even poetic style, but the writing manages to stay within a enjoyable and accessible style typical of non-fiction books. I’m not sure if my description is accurate from a literary point-of-view (I’m no expert), but here’s an example from the chapter on deserts:

When sand moves under a gathering desert wind, it seems to take on a life of its own, to become a different form of matter — like a gas, like liquid nitrogen spilling and spreading, following the ground surface. Spraying off the crest of a dune, shimmering in the light, veils of sand race and ripple, spread and vanish, their place continually taken by the next gossamer sheet, dancing, playing, celebrating. Are these jinns, the spirits of the desert? The sight is beautiful and hypnotizing in the evening sun, but if the wind gathers speed, beauty rapidly vanishes as the violence and menace of a sandstorm grows. Suddenly, it seems as if the entire mass of desert sand has sprung from the ground to hurtle with the wind. On the surface, everything is moving, even the largest grains, rolling, tumbling, kicking smaller grains into the rushing current. The sky disappears, and the howl of the wind seems amplified by its cargo of sand. The air is filled with flying sand, unbreathable.

There are many sections of ‘Sand’ that are able to communicate how dynamic and beautiful nature’s processes are. Another theme that is apparent throughout Welland’s writing is the concept of scale — both spatial and temporal — and how sand is so intimately connected with considerations of deep time and countless numbers.

In addition to stories of Earth’s geologic history that are revealed through sand, Welland devotes significant parts of the book to the seemingly countless ways in which sand intersects human civilization. This list is by no means meant to be exhaustive but will give you a flavor of some of the topics discussed in ‘Sand’:

- fundamental materials (building stone, glass, aggregates, etc.)

- the concept of sand as a powerful metaphor in thought and storytelling (e.g., very large numbers and very small things)

- importance of sand for the ecological health and safety of coastal areas

- utility of sand in forensics and crime-fighting

- reservoirs for important (and valuable) fluids

- threat of migrating sand dunes to villages/towns

- sand as an artistic medium — for drawing, sculpting, painting, writing, and more

- microchips (and, electronics in general)

- how quicksand really works

- and much, much more …

If I had to pick one thing I didn’t like about ‘Sand’ it’s the chapter on the myriad uses of sand in our lives. It is organized as an A to Z list, which, when compared to the other chapters that read more like a story, comes across as encyclopedic and a bit out of place. That said, I don’t have any suggestions for a better way to do it. Sand truly is ubiquitous and its uses are literally everywhere — if the point of the chapter was to emphasize sand’s ubiquity through a comprehensive list then the point is well taken.

The closing chapter of ‘Sand’ addresses the presence and importance of this material beyond the confines of our planet. The fact that the Huygens probe documented sand when it landed on Titan is a poignant testament to how fundamental it is in our universe (nevermind that the sand is made out of hydrocarbon ice — remember, it’s the size that makes it sand).

I highly recommend picking up a copy of ‘Sand’ if you are an Earth scientist of any kind — go ahead and make it a must-read on your 2010 list. For my readers that aren’t Earth scientists but enjoy nature writing at its best, I think you’ll really like this book as well.

Finally, I’ll leave you with one more quote from ‘Sand’ — a quote that offers a clear and succinct answer to the question of why it is important to increase our knowledge of the dynamics and history of a material like sand:

On such details does the character and habitability of our planet depend.

–

^ Make sure to check out Michael’s blog Through the Sandglass to read more fascinating stories about sand — some of which are included in the book, but many that are not.

* Michael Welland explains why there are two editions of ‘Sand’ with different subtitles on his blog here.

–

UPDATE (2/3/2010): Michael Welland has been awarded The John Burroughs Medal for excellence in natural history writing. This is very well-deserved.

This week’s Friday Field Foto is from White Sands National Monument in New Mexico and is inspired by a recent post on Through the Sandglass blog about sand dune cross-bedding in action.

As sand grains (in this case, the grains are made of gypsum) saltate along the dune surface by wind they reach the crest and begin to pile up in the ‘shadow’ of the wind. Then, every once in a while, a threshold is reached and a small flow of grains — a little sand avalanche, if you like — occurs moving a mass of grains down the slip face. This happens repeatedly and in different spots along the dune resulting in migration of the dune over time. This avalanching of sand grains is preserved as cross-stratification in the dune* and, if the geologic consequences are right, that dune will be preserved and lithified in the record as beautiful cross-bedded sandstone.

I also picked this photo for this week to get you all in the mood for a special event next week here on Clastic Detritus. Last August I posted a review of the book Stories in Stone and then a Q&A with the author David B. Williams.

Next week I will be doing a very similar event about the fantastic book Sand written by Michael Welland. Most of my readers already know about Michael’s blog Through the Sandglass, which is an outgrowth of his research on sand for his book. On Wednesday of next week I will post my review of the book and then on Thursday Michael and I will post a Q&A that we hope readers will participate in.

–

* also see this USGS site with animations of how various types of cross-stratification are formed

Papers I’m Reading — January 2010

Here is this month’s installment in the papers I’m reading series:

- Carter, L., et al., in press, Landscape and sediment responses from mountain source to deep ocean sink; Waipaoa Sedimentary System, New Zealand: Marine Geology, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2009.12.010. [link]

- Vinnels, J.S., et al., in press, Depositional processes across the Sinu Accretionary Prism, offshore Columbia: Marine and Petroleum Geology, doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.12.008 [link]

- Xue, Z., et al., in press, Late Holocene evolution of the Mekong subaqueous delta, southern Vietnam: Marine Geology, doi: 10.1016.j.margeo.2009.12.005 [link]

- Xu, J.P., et al., in press, Event-driven sediment flux in Hueneme and Mugu submarine canyons, southern California: Marine Geology, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2009.12.007. [link]

- Weissmann, G.S., et al., 2009, Fluvial form in modern continental sedimentary basins: Distributive fluvial systems: Geology, doi: 10.1130/G30242.1. [link]

- Reusser, L.J. and Bierman, P.R., 2009, Using meteoric 10Be to track fluvial sand through Waipaoa River basin, New Zealand: Geology, doi: 10.1130/G30395.1. [link]

- Van De Wiel, M.J. and Coulthard, T.J., 2009, Self-organzied criticality in river basins: Challenging sedimentary records of environmental change: Geology, doi: 10.1130/G30490.1. [link]

- Gombosi, D.J., et al., 2009, New thermochronometric constraints on the rapid Paleogene exhumation of the Cordillera Darwin complex and related thrust sheets in the Fuegian Andes: Terra Nova, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3121.2009.00908.x. [link]

- Liu, J.P., et al., 2009, Fate of sediments delivered to the sea by Asian large rivers: Long-distance transport and formation of remote alongshore clinothems: SEPM The Sedimentary Record, vol. 7, no. 4 [pdf]

–

Note: the links above may take you to a subscription-only page; as a policy I do not e-mail PDF copies of papers to people (sorry).

Friday Field Foto #100: Sandstone injectites in Patagonia

This week’s Friday Field Foto (the 100th!) is inspired by Callan’s post this morning about his recent trip to the Torres del Paine region of Chilean Patagonia. He mentioned coming across a clastic intrusion during one of their hikes on the north side of the Paine Massif. I’ve never been to that exact location but these clastic intrusions, known as ‘injectites’, are relatively common in this sedimentary basin.

I’ve probably posted these photos before but I think it’s been well over two years since then so it’s worth a re-post.

Thin-bedded turbidites and sandstone dikes, El Chingue Bluff, southern Chile (© 2010 clasticdetritus.com)

Thin-bedded turbidites and sandstone dikes, El Chingue Bluff, southern Chile (© 2010 clasticdetritus.com)

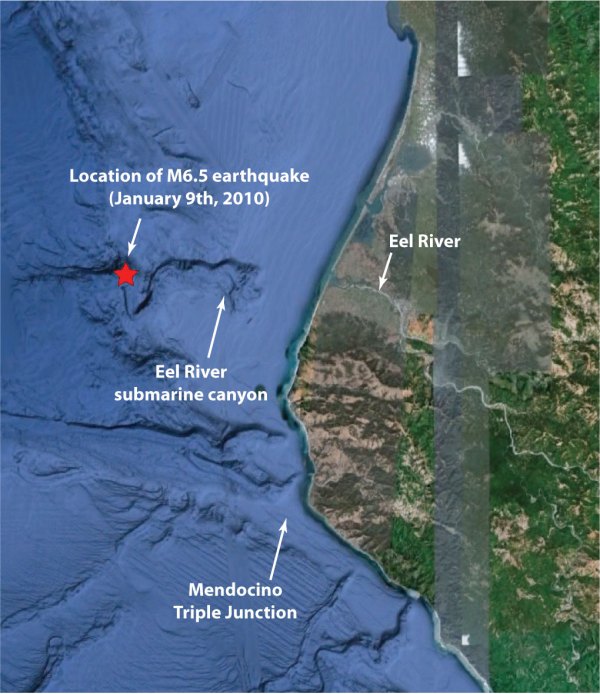

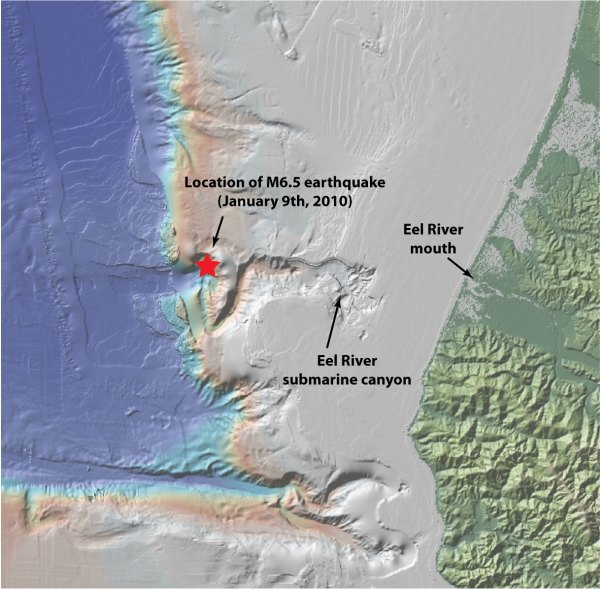

Sea-Floor Sunday #59: January 9, 2010 earthquake and the Eel River submarine canyon

This week’s Sea-Floor Sunday image shows the location of yesterday’s (January 9th, 2010) M6.5 earthquake offshore of northern California. I wanted to highlight that the location of this earthquake is almost right on the Eel River submarine canyon.

Here are some increasingly zoomed-in maps of the earthquake epicenter in relation to the sea-floor topography.

This final map below is from the GeoMapApp tool, which gives a slightly different view of the same data.

Although the head of the submarine canyon is not currently connected to the river mouth (was abandoned as sea level rose since the Last Glacial Maximum) but still receives a lot of sediment via reworking of shelf sediments.

When I saw the location I wondered if this event might have triggered a submarine sediment-gravity flow (turbidity current, debris flow, etc.), which is known to occur in this area. The Eel system is relatively well monitored so there might even be some data to address this question — I don’t have time at the moment to do the necessary research, but I will follow up in the coming weeks.

This week’s Friday Field Foto is from an area just west of Death Valley called Darwin Canyon. As you can see, there is a sharp, angular contact between two sedimentary formations — an angular unconformity.

Note person in lower right for scale.

When I took this photograph I didn’t have any specific knowledge of this geology because we were driving between stops. But 2 minutes on the google machine uncovered this fantastic web resource — Death Valley Geology: A Field Guide and Virtual Tour by Steven G. Spear from Palomar College.

The information for this angular unconformity is here and this is what they have to say about it:

The layers below the unconformity are the lower Permian Darwin Canyon formation seen at the folds up-canyon. The layers on top are Triassic marine deposits (and may correlate to similar age strata in Butte Valley). The angular discordance of the unconformity is about 20o. The age of this unconformity has been quite well dated. The youngest fossils in the beds from under the unconformity are Wolfcampian fusilinids of the Panamint Springs member of the Darwin Canyon formation. The oldest fossils from the layers above the unconformity are Guadelupian (Capitanian) brachiopods and mollusks.

Happy Friday!

Little River Research & Design — guest post

Note: This is a guest post from Steve Gough, the founder of Little Research & Design.

–

Little River Research & Design is a small “semi-profit” organization I founded in 1991. For 16 years it was mostly just me doing consulting in applied river geomorphology. In 2007, I hired three people so we could shift more from consulting to river conservation science and education. We produce high quality educational video, some compiled on this DVD, and also movable bed river models (MBMs), including the big (4 m x 1.5 m) Emriver Em4 and the smaller, portable Em2. There are now fifty Em2s in use, about half of them are at university geoscience departments. We’re now working with museums, state and federal agencies, and other universities to develop MBM hardware (including open source designs) and curriculum. We’ve developed a unique color coded by size plastic modeling media that I think will revolutionize MBM use for research and teaching; short video here (.mov file) and are also working on cool new technologies like close range photogrammetry for use with MBMs.

As part of that work we’re collaborating with ten institutions, led by Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, on an NSF CCLI proposal due soon.

If you’ve ever used a stream table for research or education, you can help us by completing this survey. You can follow our work and developments in applied fluvial geomorphology on my blog Riparian Rap.

The last two years have been a struggle—almost all our clients are tax-supported, and the economic downturn hit us hard. Thanks to Brian for use of his excellent blog, and also to you for reading and forwarding this post to colleagues who might be interested in our work.

Check out more photos of the models and of field work on LRRD’s Flickr page.