Classic Science Papers – a new blog carnival?

In case you missed it, the physics blog Skulls in the Stars challenged other science bloggers to put together an in-depth post about an old (pre-1950ish) paper in their field.

There are 25 entries that span several scientific disciplines. Three from the geoblogosphere, including me, are part of that group:

Check out the entire collection … very cool. There is talk of this perhaps becoming its own science blog carnival, which sounds like a great idea. It could also be a fun Accretionary Wedge topic at some point.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sea-Floor Sunday #20: Cascadia subduction zone

I guess I’m on a plate tectonics kick … the last few Sea-Floor Sundays have shown bathymetric (sea-floor topography) images at a scale where big-scale tectonic features are evident (see Scotia Plate, regional context of Chaitén volcano, and Gulf of California).

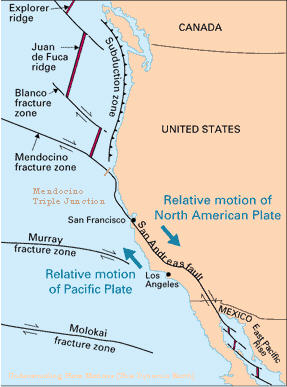

For today, I wanted to show a nice image of the Cascadia subduction zone offshore of the Pacific Northwest of the United States. First, the map (below) shows the relatively small Juan de Fuca plate and associated subduction zone for context. The Juan de Fuca plate is subducting from west to east under northwestern United States and southwestern Canada.

(© USGS)

As sea-floor mapping technology continues to improve researchers continue to learn more about submarine geology. As the resolution and coverage gets better we are able to investigate regions across a broad range of scales.

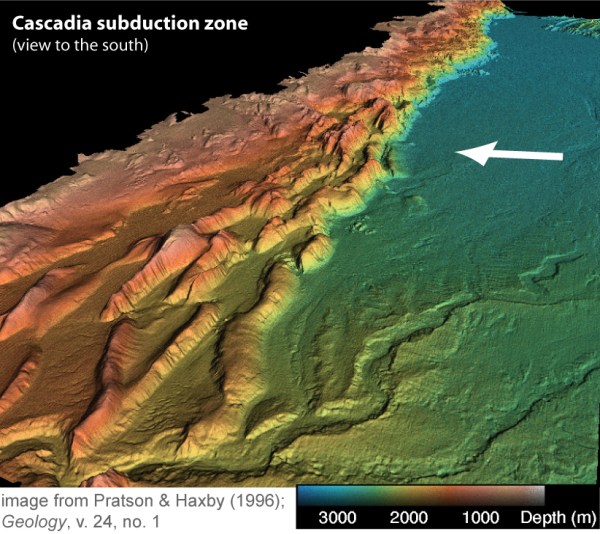

Coastal areas are mapped much more thoroughly than the open ocean because of their importance to human livelihood (and proximity for operations). As a result, many of Earth’s continental-oceanic plate boundaries are relatively well-imaged. The image below is from a paper I’ve discussed before by Pratson & Haxby in 1996 (link to paper here). This only shows bathymetry seaward of the continental shelf edge – all the black area in the upper left is the submerged continental shelf and coastline. The view is to the south and shows the Oregon part of the subduction zone.

The first thing that jumps out in this image is the belt of folds and faults that runs the length of the subduction zone in this area. This is mostly sedimentary material that is getting crumpled up as the plate subducts (from right to left on image above). As accretionary wedges go, this one is pretty dang accretionary! In fact, you can’t even see an obvious trench seaward of the fold-thrust belt. This area is so swamped with terrigenous sediment (i.e., derived from continent) that its filling in any low spot it can get to. Note the relatively flat areas between the worm-like ridges – these are basins filling with sediment. One reason why ancient accretionary wedges are so difficult to figure out is that sedimentation and deformation are occuring at the same time, which results in mind-bendingly-complex relationships.

Also note the beautiful submarine valley heading out seaward of the continental slope onto the less-deformed oceanic plate. Even though you can’t quite see it (off the bottom left of the image), you can imagine that a sediment pathway has developed cutting through the entire accretionary wedge. That’s a fun story to save for another time.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Friday Field Foto #53: Armored mud ball

I was recently going through all my field photographs from Patagonia while putting together some material for a guidebook and found a nice example of an armored mudball.

Back in February I posted a geopuzzle Friday Field Foto showing a situation where just the armor was left, but the mud had eroded out.

Today’s example is a more straightforward example. This is within a mixed mud-silt-sand matrix-supported conglomerate in the Cretaceous of southern Chile. This is within a complex of clastic injectites, which you can read about here.

Happy Friday!

–

See all Friday Field Fotos here

See all posts tagged with Patagonia here

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Columbia University physicist and author Brian Greene is the co-organizer of the World Science Festival (May 28th-June 1st, 2008 ) in New York City. Greene is a true champion of science appreciation and communication. He is still the only person I can find that talks about string theory in a way my feeble mind can grasp.

Greene and journalist Tracy Day co-founded this organization and spearheaded this festival. The mission statement for the festival states:

To cultivate and sustain a general public informed by the content of science, inspired by its wonder, convinced of its value, and prepared to engage with its implications for the future.

What a fantastic idea … and it is at the right time. I have a feeling we’ll need more of these events to combat the ever-growing anti-science movements around the world.

But … (there’s always a ‘but’) … I’m a bit perturbed about the dearth of Earth scientists that are speaking at this event.

Check out the list of speakers for the event. There are ~125 people listed and only one Earth scientist (oceanographer Sylvia Earle). Maybe there are a few more that one might include in the list of practicing Earth scientists (e.g., planetary scientist Christopher McKay), but, by and large, those that focus on the physical systems of the planet we live on are essentially absent.

There are numerous speakers from the arts (e.g., directors, choreographers, etc.) and journalism (e.g., authors, radio show hosts, etc.). There are plenty of physicists, neuroscientists, philosophers, and even a few priests. Don’t get me wrong … this is great! It’s extremely important to bring together scientists and non-scientists for an event like this where the value and excitement of science is being celebrated.

But, maybe a climatologist … a geophysicist or geologist perhaps … just one or two to add to the mix.

Just sayin’.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Source-to-Sink: The future of sedimentary geology?

Some comments and discussion in a recent post about stratigraphy motivated me to finish this post about the future of sedimentary geology, which I started a few months ago but never finished.

–

![]() In January 2008, Nature (#451) included a supplement highlighting International Year of Planet Earth, (IYPE) which is a joint initiative by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS).The supplement contains about 15 essays spanning such topics as deep Earth composition, history of geology, and several about climate-related topics. One of the essays (the only one I’ve actually read), “From landscapes into geologic history” by Philip Allen, covered a broad range of Earth surface-related topics with few words and, in my opinion, did it very well.

In January 2008, Nature (#451) included a supplement highlighting International Year of Planet Earth, (IYPE) which is a joint initiative by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS).The supplement contains about 15 essays spanning such topics as deep Earth composition, history of geology, and several about climate-related topics. One of the essays (the only one I’ve actually read), “From landscapes into geologic history” by Philip Allen, covered a broad range of Earth surface-related topics with few words and, in my opinion, did it very well.

The fact that I recently completed a graduate degree combined with the timing of this essay inspired me to think about the future of my discipline – sedimentary geology. The best way to start this post is with the opening statement of Allen’s essay:

Erosional and depositional landscapes are linked by the sediment-routing system. Observations over a wide range of timescales might show how these landscapes are translated into the narrative of geological history.

The future of many scientific disciplines, some say, is integration with other disciplines. How do different components of a system interact? Allen is advocating a more comprehensive “systems” view that has gained increasing attention, at least since I’ve been paying attention (~10 years now).*

A classic paper I’ve blogged about by Harry Wheeler (1964) touched upon this notion when he stated:

…stratigraphers must concern themselves with the interpretation of degradational as well as aggradational patterns. Conversely, the geomorphologist who ignores depositional phenomena is equally delinquent.

Wheeler mentions a couple specialties by name — stratigraphy and geomorphology. Almost 45 years later we still have these sub-fields, as we should, but I think we are appreciating the overlap and interdependence of systems more and more. That appreciation and interest is motivating researchers to investigate and unravel the interactions of the systems.

This is essentially what Allen’s essay is about … and he brings in more scientific specialties in addition to stratigraphy and geomorphology:

The growing field of study of Earth surface processes is uniting the normally disparate disciplines of solid Earth geology, geomorphology and atmospheric and oceanographic sciences.

Earth surface processes is indeed a growing field. One might argue that it’s just a different name for what we’ve already been doing. Perhaps it is … but the formalization of it (as evidenced by a journal with that name) is relatively new.

Having the discussion of what is and what is not a new discipline and how to define that is not what I’m interested in with this post. I am more interested in the bigger picture. We are we headed?

Part of this growing appreciation and interest in the entire Earth surface system, especially with regards to erosion, transport, and deposition of sediment, is an approach that has been termed source-to-sink. I’m not sure where/when that term was coined … it doesn’t really matter. Researchers have certainly been investigating and discussing source-to-sink (or less alliteratively, source-to-basin) aspects of modern and ancient sedimentary systems for a long time. But, again, it seems to me that it is gaining appreciation as an approach in and of itself more in recent years.

(© Nature)

What do we mean by source-to-sink? One way to visualize this is to think about a single grain of sand. Let’s say you got your typical quartz sand grain that is weathered out of an aging granitic outcrop. What happens along the path from liberation to ultimate deposition?

Geomorphologists primarily look at the net-erosional parts of the system (the ‘source’) and try to get clues from the landscape about tectonics. What is the rate of erosion? How does that relate to rates of uplift? Can we study the long-term evolution of a uplifting/eroding landscape and deduce the local as well as far-field tectonic history? How does the climate affect patterns of denudation? Where, when, and why does that sand grain come loose and start making it’s way down system?

Sedimentary geologists are primarily concerned with the net-depositional parts of the system, or the ‘sink’. How many times was that sand grain deposited along the way? How long did the whole journey take? How long did it remain in an intermediary location? Where is the final site of deposition before it’s buried and put into the stratigraphic record – in a river? a delta? the deep sea? Why that location for that system? What does that tell us about the system as a whole? And so on, and so forth.

Allen expresses these ideas, more eloquently than I can, when he states:

The mass fluxes associated with the physical, biological and chemical processes acting across the landscape involve the transport of particulate sediment and solutes. Sediment is moved from source to sink — from the erosional engine of mountainous regions to its eventual deposition — by the sediment-routing system. The selective long-term preservation of elements of the sediment-routing system to produce the narrative of the geological record is dictated by processes operating in Earth’s lithosphere.

What’s compelling about this as an approach is the potential for improving our understanding with respect to controls on sedimentation. Sedimentary geologists have for a long time discussed how external forcings such as climate, sea level, and tectonics (to name a few) control patterns of sedimentation. But, I would argue that we still lack a true understanding of the interactions of various external forcings. [I have a paper in press right now from some work I did on a Holocene system that attempts to address this … I’ll post about it when it’s out].

Allen also touches on factors that are intrinsic to the sedimentary system itself:

…the sediment flux signal from the contributing upland river catchment is likely to be transformed, phase-shifted and lagged by the internal dynamics of the routing system. If this is the case, how can we possibly decipher the forcing mechanisms for a particular record in deposited sediment without knowing how it has been transformed by the internal dynamics of the sediment-routing system?

In other words, if the “noise” related to the transport and deposition of our single sand grain overpowers the signal from the external forcing (e.g., climatic fluctuation) can we even detect it? This is the question at this point. I saw a talk by University of Minnesota geologist, Chris Paola, at a conference in April that concluded that, at least in some cases (and based on scaled-down experiments), the internal dynamics will indeed completely destroy the original signal.

So, where do we go from here? If we put our efforts towards characterizing and unraveling the interactions of modern and geologically-recent (e.g., late Pleistocene-Holocene) source-to-sink systems – where we have a relatively good handle on timing of paleoenvironmental changes – can we apply what we will learn to the ancient? Allen articulates this question quite well when he states:

Time transforms sediment-routing systems into geology, and like history, selectively samples from the events that actually happened to create a narrative of what is recorded. Progress in understanding modern sediment-routing systems now leaves us poised to answer the important question: how do we simultaneously use the modern to generate the time-integrated ancient, and ‘invert’ the ancient to reveal the forcing mechanisms for change in the past?

This is, of course, the fundamental goal of looking at the sedimentary record in the first place (and has been for centuries). Will a source-to-sink approach and integration with other Earth surface processes lead us down a research path worth following? I think so … but, then again, this is what I do, so perhaps I’m biased in my thinking. The real challenge, which is something almost all science will face in this century, is how to effectively integrate and synthesize complex systems while not losing the rich details.

In my opinion, this is very challenging … but it is also very exciting.

–

* In terms of a “systems” view, I’m speaking within the context of research activities … that is, conducting new science. A somewhat separate discussion would be implementation of a systems view within the context of geoscience education. This is another can of worms that perhaps my geoblogger colleagues who are educators (Kim, Ron, Callan, etc.) might want to start a thread about. Personally, I’m a strong advocate of appreciating a systems view in scientific investigation … when it comes to education, however, I think the core disciplines of geology (e.g., mineralogy, petrology, structural geology, sedimentology, etc.) are absolutely, positively necessary. In my opinion, an undergraduate requires solid training and experience in the nitty-gritty before integration and interdependence of systems can truly be appreciated. But … like I said, let’s save that for another time … or I’ll tag a willing geoblogger with that. Anybody? UPDATE: Kim over at All My Faults… started a thread about teaching Earth systems here.

Allen, P. (2008). From landscapes into geological history Nature, 451 (7176), 274-276 DOI: 10.1038/nature06586

I’m headed out for a short trip out of town, so this is really quick.

If you ever find yourself within a day’s travel of Guadalupe Mountains Nat’l Park in west Texas and southeastern New Mexico (which you should), make sure you take a day to do the Permian Reef Trail in McKittrick Canyon. Not only is it beautiful, but the trail is marked with signs explaining the geology of the area.

Today’s photo is a view from near the top of ridge looking out to the northeast. Essentially, the relief shown there is a product of going from reef crest to adjacent basin. In other words, the modern-day topography reflects the paleotopography of a reef rimming an ocean basin during the Permian!

Happy Friday!

–

see all my posts tagged with west Texas here

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Accretionary Wedge #9: Western Interior Seaway

The theme for this month’s geoscience blog carnival, The Accretionary Wedge #9, is to discuss a significant geologic event. What event (or period, or feature) of Earth history has had an effect on you and why?

The theme for this month’s geoscience blog carnival, The Accretionary Wedge #9, is to discuss a significant geologic event. What event (or period, or feature) of Earth history has had an effect on you and why?

What I did for this theme was to think back and pinpoint a moment in my education and training where I had a personal epiphany about geology. And then … what was that epiphany about?

At the risk of repeating myself, if you go back to the first Accretionary Wedge, participants discussed how they got into geoscience and why they chose that path. In my post, I discussed how enthralled I was (and still am) with paleogeography — putting the puzzle pieces back together with evidence from the rock record and reconstructing the Earth, especially the surface of the Earth. What I alluded to in that post, but didn’t talk about in detail was the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway of North America. I suppose this isn’t really an event, per se, but I guess that depends on what spatial and temporal scales one is considering.

Like many geology students in the United States, I found myself examining the Cretaceous of the Rocky Mountains during my undergraduate field camp and then in more detail a few years later during my master’s degree.

Perhaps it is so well known now … and maybe even a bit mundane. Everybody knows there was a shallow seaway cutting across the continent during the Late Cretaceous. But, if you put yourself as a newbie … a newbie not only to field geology but also to the wonders of the western U.S., when you finally put it together in your head what you’re looking at, it’s incredible!

We all hear about ancient oceans, but to stand surrounded by the rocks, the evidence, and really visualize the environment is truly an experience I can’t forget. In that sense, maybe the significant event is really my epiphany and not so much the geologic history.

~

– All my posts tagged with ‘Utah’ are about systems associated with the Western Interior Seaway

– The wonderful paleogeographic images in this post from the website of Northern Arizona University professor Ron Blakey. This site a must for any Earth history enthusiast!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Wake up, America … and stop looking for a scapegoat

Rising gasoline prices are all over the news … multiple times a day, at least in the United States. People are getting so upset that Congress decided to question oil company executives about it.

“You have to sense what you’re doing to us – we’re on the precipice here, about to fall into recession,” said Sen Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) “Does it trouble any one of you – the costs you’re imposing on families, on small businesses, on truckers?”

This sounds very nice and populist … he’s looking out for the little guy. I like Durbin and I think he generally is looking out for the general public (even if they don’t know it or appreciate it). This is an oversimplification — selling gasoline barely makes a profit (selling crude oil, on the other hand…). To say they are ‘imposing’ a gasoline price is plain wrong. Firstly, crude oil and gasoline are two different, yet obviously linked, products for sale on the market. The crude that company X produces isn’t necessarily the same that the same company refines or that the same company sells to you. Depending on where it’s produced, where the infrastructure is, etc., company X’s crude might eventually end up as gasoline in China, while, here in the States, the gasoline you purchase from company X, was once crude from a different company. Secondly, this is a global problem of supply/demand that goes far beyond the United States. Less than 10% of the world’s petroleum is produced by these major corporations — the vast majority is from the so-called ‘petrostates’, the national oil companies around the world (joint ventures among public and state-owned companies complicate these figures for sure; I honestly don’t know how, please comment if you have a reference).

So, maybe we need a completely different way of doing commerce … I don’t know. Let’s talk about that — but, this interrogation by Congress does nothing except help them save face with a frustrated public that wants to point to a single or small group of people. An enemy with a face. That’s the easy way out. Yeah, blame that guy. It’s all his fault. This is classic American blame-placing … “Hey, it can’t possibly be my fault!! It’s the government! Corporations! Conservatives! Liberals! Commies! Gays! That guy down the street! I hate that guy!”

I would argue that we have a culture of consistent blame-placing on anything but ourselves. So, am I giving oil companies a free ride? Of course not. I am more than happy to attribute a lot of our problems to major corporations … no doubt about it.

Maybe I’m being mean, but gas prices are high? Tough sh*t. We are going to have to deal with it. I’m convinced that the only way American energy consumption will change — and I mean really change — is if it hits people in their wallets. This is unfortunate, and maybe I’m just pessimistic.

So, how do we deal with it? Sure, let’s talk about ways to tax those producing, how it should work, what the impact would be, whether or not that revenue can be transferred to non-hydrocarbon technologies, and so on … but let’s also talk about the side that is consuming . It’s not a dichotomy. It’s not all or nothing. It’s complex. I know Americans don’t like complex and nuanced problems. And I know they certainly don’t like to collectively* look in the mirror and get real about consumption.

Wake up. This is real.

~

* ‘collectively’ is the key term here … I know there are plenty of individuals who have come to this realization

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Why we should be exploring our ocean

You have 18 minutes, right?

If you don’t, then make time anyway and watch this talk by ocean explorer Robert Ballard (clicking on the image below will take you to Ted.com, where you can view the video).

The speaker, Robert Ballard, does an absolutely fantastic job laying out why we should be doing more exploration of our ocean. Check it out.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~