Friday Field Foto #90: Lunar sample bag dispenser

This week’s Friday Field Foto is not really of the field … but it was in the field … ON THE MOON!

I was in Florida a few weeks back for short vacation and family reunion and we spent a day at the Kennedy Space Center checking out space shuttle exhibits and Apollo program exhibits. One of the best parts of the entire place was a room full of gear and equipment that was on the moon. While most of my family was looking at the space suits with moon dust still on them, my wife and I were checking out the super cool sample bag dispenser.

In case you can’t read the text on the placard, it says:

The pressure suits worn by the Apollo astronauts restricted their mobility, particularly their ability to bend over, while on the moon. For this reason, special tools were designed to compensate and allow them to collect rocks and soil. Smaller samples were stored in individual sample bags. Each bag had a unique identification number, so each sample could be matched to its collection site after the samples were returned to Earth. The design of these tools changed somewhat from mission to mission as experience was gained about what worked best.

Happy Friday!

Note: This post is the second of two about Stories in Stone and is a Q&A with author David B. Williams. See the first post, my review of the book, here.

Book Blogging: Stories in Stone #1 — A Review

Note: This post is the first of two about Stories in Stone and summarizes my thoughts about the book. The second post, which includes a Q&A with David B. Williams, the author of Stories in Stone, is here.

Have you ever looked at a particularly beautiful polished granite in the foundation of an office building and wondered where it came from and how old it was? Or, have you ever walked down a city sidewalk and noticed that the sidewalk was made of slabs of sandstone instead of boring concrete?

Instead of a sweeping landscape or a detailed view of sedimentary structures, my Friday Field photo from a few days ago was of houses in Brooklyn, NY. A busy street in a densely populated city is not what most of us picture when we think of “the field”. But, building stone was once part of the geological record — and it has a story to tell.

Stories in Stone: Travels Through Urban Geology by David B. Williams, published just a couple months ago (June 2009), tells those stories.

Stories in Stone: Travels Through Urban Geology by David B. Williams, published just a couple months ago (June 2009), tells those stories.

Geologists will certainly enjoy this book, but Stories in Stone is not a book about just geology. In fact, while I found learning about the geologic origins of building stone enjoyable, my favorite aspect of the book is how the geology is combined with the historical and cultural stories.

For example, the first chapter is about the reddish-brown sandstones that were used to build the beautiful brownstone buildings in New York City. Much of the building stone came from the Triassic-Jurassic Portland Formation (Newark Supergroup), which, as the following excerpt explains, was related to sedimentation in rift basins:

At least fifteen rift valleys, or basins, opened as North America, Africa, and South America pulled away from one another. The individual basins stretched from Alabama to the Bay of Fundy. Streams from adjacent hills and mountains began to carry sand and silt into the basins, including one where the Connecticut River now flows …

In addition to discussing the tectonic context of these depositional systems, Stories in Stone zooms in and talks about what turned out to be very important trace fossils in these rocks:

Nowhere on the East Coast is the record of dinosaur ascendancy better recorded than in the fifteen thousand feet of sediments that accumulated in the Connecticut River Valley. … The warm and well-watered valley was ideal habitat for dinosaurs. As they tromped around in the moist mud and sand along the valley’s streams and lakes, the great and the small left behind thousands and thousands of footprints, which remained intact as the mud hardened into rock. These tracks are one of the coolest and also most geologically important aspects of the brownstone.

Stories in Stone is chock full of fascinating geologic tidbits like this. But, as I mentioned above, how the geology is intercalated with the architectural and engineering aspects of building stone is really what this book is about and why it is a good read. For example, here’s another passage about the brownstones:

Bedding created a flat surface ideal for building blocks. Quarrymen also took advantage of bedding because the contact zone between beds is weak — relative to surrounding rocks — and is easier to pry apart. Furthermore, floods often deposited nearly pure beds of the same-sized sediments, which made the Portland rocks homogenous and easy to work with.

This book will certainly open the eyes of non-geologists to think about where building stone comes from — and, for practicing geologists, it may have a similar, but opposite, effect. That is, when I’m in the field observing and documenting the nature of bedding I may now wonder what kind of bedding contacts are optimal for making building stone! Very cool. This is what I look for in books like this — something that makes me think differently about the world around me.

The excerpts above are from the first chapter of this book, about the brownstones, which I chose because I’m a clastic sedimentary geologist. But Stories in Stone includes an incredibly diverse selection, geologically speaking, of building stone stories. In other words, it has something for everybody:

- granite (Boston and Carmel, CA)

- gneiss (Minnesota)

- coquina (Florida) — this is probably my second favorite chapter after the brownstones … you’ll learn why coquina is extremely good at defending against 18th century cannonball fire

- limestone (Indiana)

- petrified wood (Colorado) — yes, there is a building made out of petrified wood

- marble (Italy)

- slate (East Coast U.S.)

- travertine (Italy)

I’ll end my post with this passage, which is in the concluding chapter about travertine, but I think it applies well to all building stone:

People further relate to rock as a building material because they intuitively sense the link between stone and earth around them. Even if they can’t tell the difference between granite and marble, they know that building stone has a history and a story. No manufactured building material can provide the deep connection to place that stone does.

So, if you aren’t a geologist and have ever wondered about the geological stories behind building stone you will thoroughly enjoy this book. If you are a geologist (which most of my readers are) you will enjoy Stories in Stone because it very eloquently weaves fundamental geology into a larger fabric of architecture, history, and culture.

–

To learn more about this book, check out this post for a Q&A with the author David B. Williams.

Friday Field Foto #89: Triassic sandstones in Brooklyn, NY

Hey, wait … this photo isn’t from the field … it’s of a building in an urban area! Well, it might not be the ‘field’ that we all think of — that is, rocks in their natural habitat — but they are still rocks and they still have a geological story to tell.

This week’s Friday Field Foto is designed mostly as an announcement for a special event next week. Monday I will post a brief review of the book Stories in Stone: Travels Through Urban Geology. Tuesday, I will have David B. Williams, the author of Stories in Stone, here on Clastic Detritus for a Q&A, which will include David taking questions from the comment thread.

David’s stop here on Clastic Detritus is part of the Stories in Stone ‘virtual book tour’ — I will post the full schedule of his ‘tour’ next week.

So, what’s the geological story of the brownish sandstones in these buildings? Check back Monday to find out!

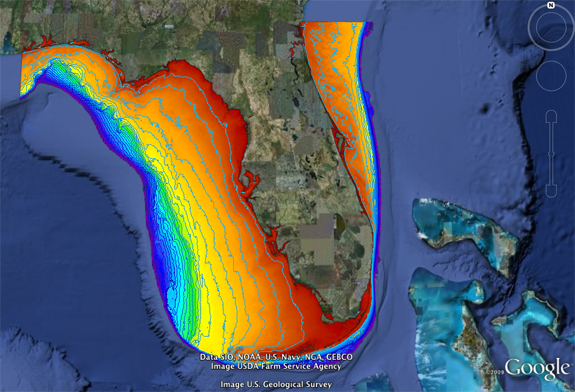

Sea-Floor Sunday #52: Florida bathymetry KMZ file

This week’s Sea-Floor Sunday highlights the Florida peninsula and surrounding waters. I chose Florida this week because I was just there for a family reunion and vacation.

The image is a screen grab from GoogleEarth. If you go to this USGS page you can get the .kmz file and view it in GoogleEarth yourself.

Speaking of GoogleEarth, the Where on (Google)Earth? series is alive and well and making it’s way around the blogosphere again. Looks like Silver Fox won the most recent.

Drain the Ocean (on Nat’l Geographic Channel)

Most of my readers know that I have a passion for submarine geomorphology (e.g., the Sea-Floor Sunday series). I got excited the other day when I came across some news while surfing around some geoblogs* about a TV program on the National Geographic Channel called Drain the Ocean. As you might imagine from that title, the show is focused on our planet’s submarine landscapes, or seascapes.

What does the sea floor look like when the water is ‘drained away’? Some TV programs that deal with geology or oceanography have touched on the nature of the sea floor, but it is almost always within the context of biology. Don’t get me wrong … I love learning about marine biology, especially of the deep sea, but I’m usually left wanting more about the physical environment. Looks like this show might be able to deliver.

Drain the Ocean is on this coming Sunday (August 9th, 2009) on the National Geographic Channel. Unfortunately, I do not have that channel … but a friend of mine is DVRing it or maybe it’ll be on Netflix soon.

In the meantime, check out their website — they have a neat little interactive map previewing some of the sites they will discuss on the program.

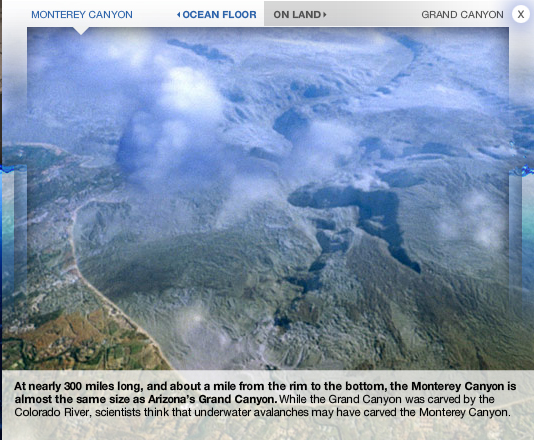

credit: http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/ (cllick on image to go to site)

The image above is from their interactive map showing how the Monterey submarine canyon is similar in scale to the Grand Canyon. Cool.

If you check out the show, blog about it, and then put a link to your post in this thread.

–

* via the blog Sedimentary Soliloquy

My Favorite Things

This summer has been busy. I’ve got a bit of traveling this week, but after that I plan to finish up a few posts and will also have a ‘special event’. Stay tuned.

In the meantime, check out the classic John Coltrane version of My Favorite Things (Rodgers & Hammerstein).

The soprano sax used to be cool — but then someone came along and completely ruined it.

Sea-Floor Sunday #51: Animation of Lau backarc basin with subsurface tomographic images

This week’s Sea-Floor Sunday is from a very cool website summarizing some research affiliated with the Ridge 2000 Program, which focuses on oceanic spreading ridge systems.

The below image is a screen-grab from a short animation that shows the bathymetry of the Lau Basin area (see general map of region on this post) combined with seismic tomographic images of the subducting Pacific Plate. This still image doesn’t do the visualization justice … click on the image below to go to the site and view the movie (it’s the third bullet-point in list).

Screen grab of short animation showing perspective views of Lau Basin bathymetry and subsurface tomography (credit:http://ridgeview.ucsd.edu/index_lau.html)

Here is some information from the site about what data is included in the animation:

Movie of the spatial relationship of different data types near the … the Eastern Lau Spreading Center. For reference we include a mesh that represents the center of the subduction zone earthquakes, which extends to a depth of ~700 km. Other data include active volcanoes (orange cylinders), bathymetry (colored by elevation, vertical exaggeration 6X, spanning longitudes 180-188 and lattitueds -23 to -14), and historic earthquake data (pink spheres). The relatively shallow vertical cross-sections are long-axis multichannel seismic (MCS) data and the large scale red/blue/green/yellow verticle cross-sections are tomographic images, where the blue colors represent fast seismic velocities (likely cold mantle) and the orange/red colors represent slow velocities (likely warm mantle or melt regions).

Check it out.

~

Related to this area … Kevin Z. of Deep Sea News fame mentioned in his Twitter feed yesterday that he and colleagues have a paper out that deals with distribution of various fauna at hydrothermal vent sites along the Eastern Lau Spreading Center.

Sorry that the blogging has been sparse of late … been busy with work, some travel, and summertime good times.

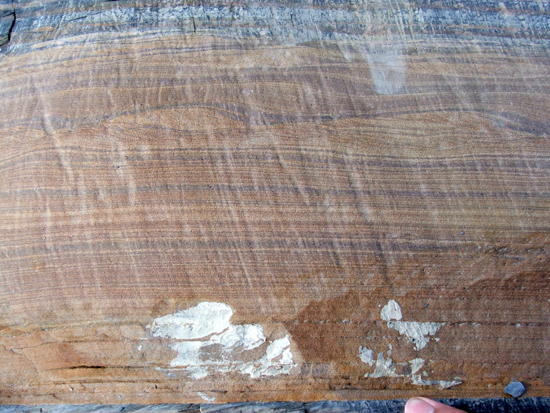

This week’s Friday Field Foto has essentially the same title as this one from a couple months ago. But instead of Eocene rocks (55-34 million yrs old) in the French Alps, the photo today is of Neoproterozoic strata (in this case, ~600 million yrs old) in British Columbia, Canada. Notice my finger at the bottom of the photo for scale.

Those ripples are gorgeous! So nice that the photo below zooms in a bit more.

In case you’re wondering … these rocks are dipping vertically, so with these photos you are standing on them and looking straight down at a cross section. The ‘scuff marks’ cutting across the bedding are glacial striations. In fact, the very recent glaciation (the glacier is still there) is part of the reason these exposures are so beautiful — they’ve ‘cleaned off’ all the vegetation and soil. I love it when they do that.

Happy Friday!

The July 2009 issue of Journal of Sedimentary Research includes a paper I’m a co-author on about some sedimentological work we did in southern Chile. If you’ve been following this blog you know that we’ve done a lot of work on the deep-marine strata in this area, but overlying the deep-marine succession is a deltaic and shallow-marine formation that, until now, hasn’t been looked at in detail. This paper, which is hopefully the first of a series about this formation, summarizes work we did investigating the stratigraphic evolution of ~300 m (1000 ft) thick interval spanning delta-front to coastal plain depositional environments.

Hopefully I will find some time soon to blog about these rocks in more detail (which I also said about this paper last month) … but, in the meantime here is a photograph of part of the outcrop. The steeper sandstone cliffs near the top of the photo are about 15 m (50 ft) tall to give you a sense of scale.

This photograph nicely shows the stacking of different depositional environments all in one view.