I realize it’s been pretty quiet on this blog for a few weeks — I was doing some traveling (mostly for work but with some fun thrown in there as well). But now that I’m back and have returned to the “normal” state of busy-ness I should be able to get a few posts out over the next week or so.

In honor of the NHL playoffs starting this week (go Sabres!), this week’s Friday Field Foto heads north to the Canadian Rockies. I was lucky enough to go on a trip back in 2008 to look at some Neoproterozoic (~600 million years old) turbidite deposits exposed in the mountains near McBride, British Columbia.

These strata are dipping nearly 90 degrees (stratigraphic up is to the left in photo above) and have been cleaned off by glaciation. In fact, you can see the small Castle Creek glacier in the background. The value of this outcrop is that you can hike around on a cross section of the stratigraphy and walk individual beds out for hundreds of meters.

The recent glaciation combined with just the right amount of metamorphism (i.e., not much) has resulted in stunning exposures of the fine-grained deposits, which are typically not as nicely exposed as the coarser-grained deposits.

Happy Friday!

Friday Field Foto #107: Wind ripples on the beach

This week’s Friday Field Foto is of some nice wind ripples on a beach in Kaua’i.

That’s it … that’s all I got today.

Happy Friday!

What do you think of the ‘Anthropocene’?

I was sitting here reading this and thinking to myself — ‘I wonder what other geoscientists think about this?’ — at which point I remembered I could just ask you all through this blog!

The question of whether or not we need to formalize a new geological time period (or, I guess ‘epoch’, in this case) that reflects the significant influence of human activities on the planet’s processes comes up every now and again these days. Numerous proponents of establishing an ‘Anthropocene’ authored an article in GSA Today in 2008 (pdf), which resulted in some discussion on geology blogs.

This latest press release refers to another paper by the same authors, J. Zalasiewicz*, M. Williams, W. Steffen, and P. Crutzen, in the April 2010 edition of Environmental Science and Technology called “The new world of the Anthropocene”. This is one of several essays in a special issue marking the 40th anniversary of the first Earth Day in the U.S.

I won’t go over their arguments here — you can read it for yourself if you haven’t already. What I’d like to know is if anybody is using this term? I haven’t seen it formally used — that is, I haven’t seen it in print in a technical paper. But, I have seen it popping up in talks here and there in the last year or so. And I don’t mean a presentation about whether or not we should use the term ‘Anthropocene’, but a talk that simply uses it just like any other time period. I suppose that makes sense — most authors steer clear of using ‘unofficial’ terms in their papers — or, if they do, the peer-review process catches it. But, in a talk, people are a bit more free to use such terminology.

Then there is the whole problem of where to put the Holocene-Anthropocene boundary. While many think of the industrial revolution and its effects on the global climate as an obvious starting point, others, like Ruddiman in his book Plows, Plagues, and Petroleum, argue that an earlier revolution — the agricultural revolution had a significant influence on climate patterns through land use changes. This would push the beginning of the Anthropocene to several thousand years ago. While such issues with the placement of the boundary would obviously have to be reconciled if it were ever to become a formal term we can still ponder and debate the utility of the term ‘Anthropocene’.

I’m trying to think if I have used ‘Anthropocene’, even just in casual conversation. If I did I’m sure I said it with a look on my face like “yeah, that’s right, I just said ‘Anthropocene'”. The term I do use for my Holocene research is ‘pre-anthropogenic’. For example, if discussing the history of sediment flux of a river during the Holocene it is useful to know at which point there is significant anthropogenic influence (e.g., building a dam).

So, what do you all think? Do you think formalizing this would be valuable? Does the whole affair make you want to throw your computer out the window in frustration? Are you apathetic? Note: I’m mostly asking those who would actually use the term as part of their research, writing, or reporting.

Even if we don’t establish formal terminology with the ICS and don’t actually use this particular term it seems to me that the entire exercise gets us thinking and talking, which is always a good thing.

–

* As an aside, I read Zalasiewicz’s popular book The Earth After Us last year and enjoyed it immensely. It’s whimsical, thought-provoking, and a pleasure to read — I definitely recommend it.

What am I working on right now?

This month’s installment of the geoscience blog carnival, The Accretionary Wedge, which you can find here on the Geology Happens blog, asked potential participants these questions:

This AW is to share your latest discovery with all of us. Please let us in on your thoughts about your current work. What you are finding, what you are looking for. Any problems? Anything working out well?

Because I work in the private sector I do not (and will never) blog about the work I do on a daily basis in any detail. In fact, Clastic Detritus is designed to be completely disconnected just so there is no confusion. Read the disclaimer page for more.

What I do blog about, however, is my published research — this is the stuff that is out there for the scientific community to read and evaluate so I feel that this blog can be an additional venue for sharing it. And, although this work was submitted many months ago and maybe not the very latest, it is a good representation of my current research interests and activities.

As my research interests page states, in the most general sense I’m interested in utilizing the sedimentary record to investigate and understand past and present Earth conditions. The sedimentary record is a representation of Earth surface processes through time and, as such, can be analyzed to reconstruct ancient environments as they relate to tectonic activity, climatic and sea-level fluctuations, oceanic conditions, and intrinsic dynamics of depositional systems.

I specialize in the study of submarine channel and fan systems, which are some of the largest accumulations of detrital material on Earth (e.g., Bengal submarine fan). Sand, silt, and mud that is eroded from the continent and the continental margin is deposited out into the deep sea by submarine sediment gravity flows called turbidity currents. If you’ve been reading this blog for a while you are well aware of my love of all things turbidite related!

I’m mostly interested in using these deep-sea sedimentary records to answer questions about the volumes, rates, and distribution of detritus that is transferred across continental margins. Essentially, I want to use the patterns we observe and measure in the stratigraphic record and relate it to fundamental processes such as plate tectonics or paleo-environmental conditions. A very interesting debate in the stratigraphic community is how to (or even if we can) unravel the extrinsic vs. intrinsic controls on the observed patterns — more on that another time. To try and address these questions my colleagues and I are analyzing both ancient and modern systems.

–

Ancient Deep-Sea Sedimentary Systems

In some cases the history of sedimentary basin development is followed by mountain-building processes, which results in the preservation of sediments deposited 10s to 100s of millions of years ago in outcrops now exposed on the Earth’s surface. The value of investigating outcrops is that the details of the system at the scale of individual beds (a few centimeters) to packaging of those beds (i.e., stratigraphy) at many kilometers is on full display. One such system that I spent several years working on (and am still working on) is the Magallanes sedimentary basin in southern Chile. These rocks were deposited in the Late Cretaceous (~70-80 million years ago) in a deep foreland basin that developed adjacent to the paleo-Andes.

Because I’m interested in understanding these systems at multiple scales — that is, what controls the character of the beds? what controls how multiple beds stack? what controls the distribution of detritus at the basin scale? — I looked at these strata at different scales. To get at some of the sedimentological details and stacking patterns at the outcrop scale I investigated a particularly well-exposed outcrop at a mountain called Cerro Divisadero. I’ve already blogged about this study, which was published in Sedimentology, so I won’t repeat it here.

So, that study looked at patterns from the centimeter- to kilometer-scale, but what about much larger patterns — for example, at the scale of the entire basin (10s to 100s of kilometers)? What’s cool about that question is that, in addition to integrating the mapping and characterization of the entire region, we looked at the microscopic level for answers. I published a paper in Basin Research (currently in the ‘early view’ here) that summarizes the results of analyzing the ages of zircon grains extracted from these sedimentary rocks. I’m still working on a blog post that discusses this work in more detail, but to make a long story short, the detrital zircon record help constrain the timing of significant tectonic activity in the adjacent mountain belt. This tectonic activity (in this case, the emplacement of thrust sheets) had a profound effect on the basin-scale stratigraphic patterns.

But not all ancient sedimentary basins are now uplifted into mountains — in fact, a lot are technically still sedimentary basins. That is, the ancient sediments are buried very deeply (sometimes up to several kilometers!) by younger deposits. Investigating the subsurface utilizes an entirely different suite of tools (e.g., seismic-reflection data), but the fundamental questions are the same.

–

Modern Deep-Sea Sedimentary Systems

When discussing sedimentary systems from a stratigraphic point of view, ‘modern’ refers to those that are still actively receiving and distributing sediment and continuing to evolve. This commonly equates to systems active during the past glacial and current interglacial climate cycles — or, the past 10,000 to 30,000 years. In other words, even if a turbidity current hasn’t occurred for a several hundred years we will still refer to the system as ‘modern’ because the depositional patterns from geologically recent activity is still in place.

Because one of my goals is to understand how sedimentary systems respond to the myriad interacting factors that control them, investigating modern systems offers the chance to establish relationships that are impossible with ancient systems. For example, although geochronometric approaches continue to improve, I highly doubt it that we’ll be able to constrain the timing of individual depositional events at the scale of few hundred years for strata that are 100 million years old. Let’s put it another way — I challenge you geochronologists out there to accomplish that! :)

Context is also critical. Ancient sedimentary systems are only partially preserved — we have to make inferences and interpretations about the nature of source areas that have long since eroded. By comparison, modern sediment dispersal systems are laid out in all their glory for us to study. For example, when characterizing ancient deep-sea sediments we commonly make an interpretation that the deposits represent a submarine channel. Depending on data the degree of confidence of such an interpretation can be high or low. Well, with modern systems, we don’t have to interpret some of those fundamental aspects — we simply know if we are looking at a channel (as long as the bathymetric mapping is good enough, of course). Given this context we can then ask some more specific questions about the system.

I published a paper last fall in GSA Bulletin about the depositional history of a modern submarine fan system offshore southern California. We integrated high-resolution mapping of the fan with a sediment core from which we obtained radiocarbon dates. We were able to constrain the timing of sedimentation for the past 7,000 years very well and saw a nice relationship to independent records of paleoclimate in southern California. This is another study that I have a blog post in draft stage that I hope to finish soon. Stay tuned.

–

Integration: Characterizing Sedimentary Systems from ‘Source to Sink’

In recent years researchers have been emphasizing ways to integrate observations and measurements from different segments of sedimentary systems — from erosion-dominated mountainous areas to deposition in rivers and floodplains and, ultimately, to sediment ‘sinks’ in coastal deltas or deep-sea basins. I wrote a post about this approach a couple years ago after reading a very nice essay by Allen in Nature, which I highly recommend.

Read that post and Allen’s essay for more, but what I’ll comment on here is some work that I am doing right now that fits nicely within the source-to-sink framework. One way to investigate how sediment source areas relate to the sediment sink areas is to look at rates of erosion and rates of deposition. Some relatively new methods of dating cosmogenic nuclides of exposed bedrock surfaces and/or sediments is helping geomorphologists constrain erosion rates. How this exactly works is something I am still learning myself (check out this article that explains it better than I could).

Some colleagues of mine did some preliminary work using cosmogenic-nuclide-derived erosion rates and compared them to deposition rates in offshore segments of the dispersal system. The preliminary results were promising so we decided to expand the dataset and we are currently awaiting the results.

I could go on but this post is already way longer than I planned and is mostly my stream-of-consciousness ramblings. I’m going to cut myself off here! I hope it’s not too confusing and if you’ve read this far you are either really interested in what I’m working on and/or are really bored!

Crazy busy this week so just a quick Friday Field Foto today.

This shot is of the Russian River mouth along the central Californian coast — a short drive north of the San Francisco area.

I’ve showed a similar view of this river mouth (taken on the same day) and include a bit of basic information and maps on this post if you want to learn a bit more. If you look carefully you can also see a bunch of sea lions (or are they seals?) chillin’ on the river-side of the beach.

Happy Friday!

Arches National Park iPhone App

UPDATE (July 2010): In hindsight I suppose this is predictable and I should have known better, but because of this post I’ve been inundated with e-mails from other app developers asking me to review and/or write a post promoting their product. While I think such information could be useful for many of my readers I do not want this site to become a product review site. In other words, this post was the first and last post of it’s kind — so, if you are a developer please do not e-mail me about writing a review. Thanks!

–

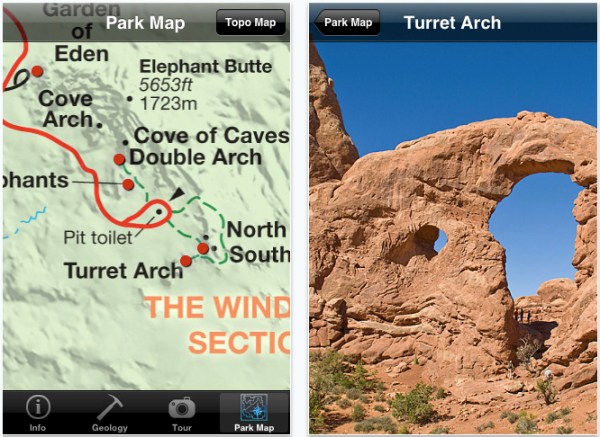

Several weeks ago the folks at Tasa Graphic Arts, Inc. asked me if I’d take a look at their Arches National Park iPhone app and blog about it — whether it was positive or negative. I absolutely love my iPhone and am always on the lookout for interesting applications, especially ones related to geology, so I agreed to take a look at it.

I already have Tasa’s geotimescale app, which I like very much for its simplicity and utility as a quick reference so I was interested to see how this app, one that is specific to a region, was done. Overall, this is a great app. Sure, I would’ve liked to test this app while actually visiting Arches Nat’l Park but, alas, I couldn’t get out there for a weekend trip :)

I’ve included a couple screenshots below that I grabbed from the iTunes page for this app. As you can see at the bottom of the screenshot, the app is divided into four sections — info, geology, tour, and park map.

The user can take a virtual tour of the geologic features of the Park by choosing a location or topic and hit ‘play’, which will go through a series of images with some audio narration. The ‘tour’ and the ‘park map’ are the best parts of the app in my opinion. The tour includes seven regions and >30 specific locations. But the best part is that the ‘map’ section lets you access this information by clicking on a part of a map (as seen in the left image in the screenshot below).

Is this app perfect? No, of course not — no mobile app is. One thing that I’d like to see improved in future versions is a better interface for the geologic map. Ideally, it would be nice to be able to zoom in or out and have the resolution of the mapped geology change*. I’m not saying this would be easy to implement — I’m sure this is a significant challenge — I’m simply communicating what it is I would like to see improved.

Finally, some may balk at the price of the app — at time of this writing it’s currently listed at $5.99. Hey, I like free (or nearly free) apps as much as the next person but, at the same time, if paying a bit more (and still quite modest) leads to better products then I’m willing to do it. There is easily $6 worth of information in this app.

In summary, I definitely recommend this app for anyone who is planning a trip to Arches soon. While I don’t think this app would be able to replace a good collection of guidebooks and old-fashioned hard-copy maps, it would make a great addition to those resources.

–

* this also goes for the Geograph series of U.S. state geologic map iPhone apps from Integrity Logic (I have the California one)

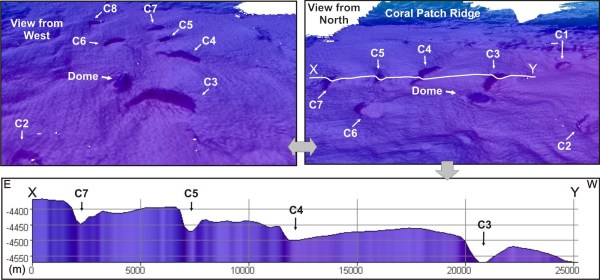

Sea-Floor Sunday #62: Giant scour features in Gulf of Cadiz

This week’s Sea-Floor Sunday image is from a geoscience blog that I saw for the first time a few months ago — The Lisbon Structural Geologist, which is written by Filipe Rosas, who is — you guessed it — a structural geologist in Lisbon, Portugal. It’s a great blog that you should add to your feed if you haven’t already.

A few days ago Filipe posted some images from a paper he is a co-author on now in press for Marine Geology that summarizes mapping and characterization of the deep sea floor in the Gulf of Cadiz. The features of interest are some rather large erosional scours (5 km across) that remind me of scours on the Monterey submarine fan that I’ve posted about here.

Scour features on sea floor near Gulf of Cadiz (figure from Duarte et al., in press, Marine Geology)

Check out Filipe’s post about these features here — or go directly to the Duarte et al. Marine Geology paper in press here.

Papers I’m Reading — March 2010

I still haven’t actually read everything I listed for last month … but, here is this month’s installment in the papers I’m reading series anyway:

- Henriksen, S., et al., in press, Relationships between shelf-edge trajectories and sediment dispersal along depositional dip and strike: a different approach to sequence stratigraphy: Basin Research, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2117.2010.00463.x. [link]

- Shirai, M., et al., in press, Depositional age and triggering event of turbidites in the western Kumano Trough, central Japan during the last ca. 100 years: Marine Geology, doi: 10.1016.j.margeo.2010.02.015. [link] — note: their main conclusion is that the vast majority of turbidite deposits can be tied to floods or storms; only one correlated to an earthquake

- Ito, M., in press, Are coarse-grained sediment waves formed as downstream-migrating antidunes? Insight from an early Pleistocene submarine canyon on the Boso Peninsula, Japan: Sedimentary Geology, doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2010.02.006. [link]

- Tucker, G.E. and Bradley, D.N., 2010, Trouble with diffusion: Reassessing hillslope erosion laws with a particle-based model: JGR Earth Surface, doi: 10.1029/2009JF001264. [link]

- Migeon, S., et al., in press, Lobe Construction and sand/mud segregation by turbidity currents and debris flows on the western Nile deep-sea fan (Eastern Mediterranean): Sedimentary Geology, doi: doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2010.02.011. [link]

–

Note: the links above may take you to a subscription-only page; as a policy I do not e-mail PDF copies of papers to people (sorry).

Friday Field Foto #105: Basalt channel

This week’s Friday Field Foto is another shot from my recent trip to Hawai’i — I’ve been sitting in my office working very hard lately and catching myself daydreaming about being in this paradise.

On one of the days we spent on the Big Island we did a 6-hour hike exploring around Mauna Ulu in Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park. Much of the area was covered by lava flows from the 1970s. Walking around on this new land is a surreal experience.

One of my favorite features was this lava channel frozen in time snaking its way down the hill.

I know very little about volcanology but, in my head I picture something like this:

Pu'u O'o lava channel (credit: http://www.lpi.usra.edu)

Happy Friday!

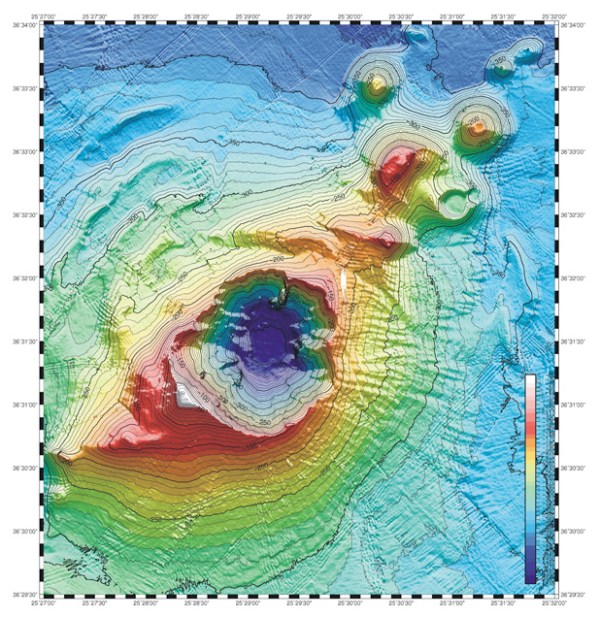

Sea-Floor Sunday #61: Kolumbo submarine crater

This week’s Sea-Floor Sunday image is of a submarine volcanic complex in the Aegean Sea. This image and much, much more about the geology of this area can be found on this page of the NOAA Ocean Explorer website.

Map of the Kolumbo submarine crater and other submarine cones on the north-east trending Kolumbo volcano-tectonic rift (figure courtesy of http://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov; click on image to go to original)

I like this image because it combines bathymetric contours, color, and shaded relief all into one beautiful map. Make sure to check out the rest of the images on this page — there is also a seismic-reflection line showing the submarine pyroclastic flow deposits on the flank of the volcano.