Wednesday potpourri of the geoblogosphere

I’ve been quite busy and traveling a bit so I haven’t been keeping up with reading everything in the geoblogosphere. Here are just a few interesting posts out there from recent days:

- Through the Sandglass — 80 Miles of Sandberms?? Experts Express Doubts … — Michael Welland highlights a recent article discussing plan to create artificial barrier islands in front of Mississippi River delta to help protect delicate wetlands along coast. This is a problem of sediment budget — how much and from where would they get the sand to create these islands? And how long would such artificial islands last? Some think that a single storm could wipe them out.

- Highly Allochthonous — The Hydrogeology of Yellowstone: It’s All About the Cold Water — Anne Jefferson has a really nice post discussing a recent paper in Journal of Hydrology that deals with the role shallow and cold groundwater plays in the Yellowstone region.

- Dave’s Landslide Blog — David Petley continues his amazingly comprehensive reporting, blogging, and explaining of the Attabad landslide in Pakistan — this is an interesting geologic story that changes daily.

- Mountain Beltway — Callan Bentley has a nice diagram explaining difference between a fill terrace and a strath terrace.

- Wooster Geologists — Check out a series of recent posts chronicling their geologic and paleontologic field work in the southern United States.

- Sandbian — Remember the geology blog Antimonite? The author of that blog from a few years ago, a geology graduate student in Sweden, has started blogging again here. Check it out.

Do we need to capture and store CO2 from coal plants to meet emissions reduction targets?

I wrote a very brief article for EARTH magazine addressing this question for their ‘Voices’ series. It is posted here and will be in the print edition in a couple months.

Feel free to use this post for any comments and discussion about it — however, I am doing some traveling through the weekend so I may not be very responsive until next week.

Exporting environmental catastrophes

At the time of this writing the leaking/spilling of an oil well operated by BP in the northern Gulf of Mexico has yet to be fully contained. Crews are right now in the process of lowering a 100 ton concrete and steel container onto a part of the damaged seafloor infrastructure that is leaking. Because the blowout of a well in 1,500 m (5,000 ft) of water is unprecedented, the methods to containing it have never been tried. I surely hope this works and wish the crews working 24/7 on this problem the best.

There are so many articles, reports, blog posts, and commentary about this event I won’t try to summarize them all here. Instead, I’d like to highlight one particular column that really spoke to me — ‘A Spill of Our Own’ by Lisa Margonelli in the May 1st, 2010 New York Times. In 2007 Margonelli published a book called ‘Oil on the Brain’ discussing how much oil America consumes and the journey this resource takes from its formation to the pump. I haven’t read the book myself but it has now leap-frogged up to the top of my to-read stack.

Within a few days of this event making the front pages the debate about whether or not to lift moratoria on domestic offshore drilling was reinvigorated. There has always been something about this debate that is unsatisfactory to me — that we are rehashing the same-old arguments and can’t seem to get anywhere. Margonelli’s column distills it down to a very simple statement:

Effectively, we’ve been importing oil and exporting spills to villages and waterways all over the world.

We import oil and export spills. Plain and simple. This is the NIMBY (not in my back yard) effect writ large. The combination of increasing demand/consumption with the collective NIMBY attitude results in the exploration and production of oil in areas of the world that lack the environmental regulations the U.S. has:

Kazakhstan, for one, had no comprehensive environmental laws until 2007, and Nigeria has suffered spills equivalent to that of the Exxon Valdez every year since 1969. (As of last year, Nigeria had 2,000 active spills.) Since the Santa Barbara spill of 1969, and the more than 40 Earth Days that have followed, Americans have increased by two-thirds the amount of petroleum we consume in our cars, while nearly quadrupling the quantity we import.

In 2008, the United States consumed nearly 20 million barrels of oil per day and produced approximately 7 million barrels oil (equivalent) per day (see this EIA report for the detailed breakdown). In the chart below that gap between consumption (red line) and production (gold line) illustrates this deficit. As a result, our net imports (blue line) have increased over time.

So, here’s a wild thought to provoke discussion — what if it was required that the amount of oil we consume had to be matched by domestic production? What if we decided to recognize our NIMBYness and be responsible? In other words, what if, as a society, we decided to stop exporting our petroleum-related environmental problems to other countries?

So, here’s a wild thought to provoke discussion — what if it was required that the amount of oil we consume had to be matched by domestic production? What if we decided to recognize our NIMBYness and be responsible? In other words, what if, as a society, we decided to stop exporting our petroleum-related environmental problems to other countries?

Isn’t this what the ‘drill, baby, drill’ crowd is arguing? No. Their main arguments are job creation and energy independence; they are not arguing that we need to take responsibility for the inevitable environmental consequences. In fact, one of their main selling points is that the impact on the environment nowadays is negligible. Additionally, they fail to take into account the negative impact on existing jobs and economies accidents like this have when they claim how this will help the economy.

Environmentalists might react to what I’m saying with ‘How could you possibly suggest we increase domestic production in light of this catastrophe!?’ What I’m saying is that maybe if Americans are forced to actually live with the consequences of their consumption — that is, to have oil derricks in their backyard — might we then stop postponing and finding excuses to transition to new energy sources?

American’s support for domestic offshore drilling is very likely falling significantly as they watch the sludge lap up onto the Louisiana coast and as they see with their own eyes how this disaster affects the economy and livelihoods of people on the Gulf Coast. I don’t want to minimize the ecologic catastrophe and local economic impacts that are unfolding, but as we focus on these aspects are we sweeping the consumption issue under the rug?

This image of an oil field in the Caspian Sea is what ‘drill, baby, drill’ looks like. This is an example of ‘drill here, drill now’. For those advocating the kind of aggressive increase in domestic production it would take to attempt to close the production-imports gap (if that’s even possible) then please volunteer to have this in your backyard. If you do then I applaud you — at least you’re being consistent.

This image of an oil field in the Caspian Sea is what ‘drill, baby, drill’ looks like. This is an example of ‘drill here, drill now’. For those advocating the kind of aggressive increase in domestic production it would take to attempt to close the production-imports gap (if that’s even possible) then please volunteer to have this in your backyard. If you do then I applaud you — at least you’re being consistent.

Worse, are those that agree this is not something they’d want in their backyard but, at the same time, they refuse to reduce consumption and/or complain about those who propose laws or regulations designed to reduce consumption. You can’t have your cake and eat it too.

However, we need to accept that oil is, and will continue to be, an important resource. Even the most aggressive proposals to ramp up non-oil fuels to the scale it needs to be recognize that oil will be part of the mix for decades.

So, in addition to images of devastated wildlife and fisheries shouldn’t the media also be showing graphs like the one above? Instead of the predictable, made-for-cable-TV debates pitting someone chanting ‘drill, baby, drill’ against an environmentalist wouldn’t it be nice to discuss the bigger picture of oil consumption, dependence, and associated risks?

Margonelli concludes her column with this sentiment:

I hope the Deepwater Horizon spill doesn’t get bad enough to join Santa Barbara and Exxon Valdez in the rogues’ gallery of huge environmental disasters. But it should galvanize us to address the real problem with oil spills — the oil.

–

note: as I was drafting this post I came across this commentary from the blog 4.5 Billion Years of Wonder, which is worth checking out.

Friday Field Foto #111: Mauna Ulu steam vents

This week’s Friday Field Foto is from a trip my wife and I took earlier this year to Hawai’i. We spent three days on the Big Island exploring Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park.

The photo below is from a great six-hour hike we did around Mauna Ulu. The landscape is surreal — as we hiked on 40-year old rocks we came across these small steam vents.

Happy Friday!

Friday Field Foto #110: Thin-bedded turbidites of Cretaceous Great Valley Group, California

This week’s Friday Field Foto returns to what makes up the majority of my field photograph collection — turbidte outcrops.

Unfortunately, I could not find the notebook that corresponds to this particular field trip and don’t have the exact XY location (someday I’ll have a camera with a GPS). But, this is a road cut along highway 16 near Cache Creek Regional Park in central California. These are Cretaceous strata that are now uplifted along the eastern flank of the Coast Ranges. Note the road at bottom of the photo for a sense of scale.

As you can see this is pretty thin-bedded, fine-grained stuff — mostly siltstone with a few more resistant sandstone beds. We know they are deposits of sediment gravity flows (i.e., turbidites) but what depositional environment do you think it is?

Happy Friday!

Geological heroes: Marine geologist Bill Normark

The theme for this month’s geoscience blog carnival, The Accretionary Wedge, is geological heroes. Callan Bentley of the Mountain Beltway blog is hosting:

I invite all participants (geobloggers and geoblog readers alike) to contribute stories of their heroes. It’s time to pay tribute to the extraordinary individuals who helped make your life, your science, and your planet better than they would otherwise have been.

–

There are many people that I could call a “hero” but one that had a significant influence on me is marine geologist Bill Normark (1943-2008). Bill spent the majority of his career with the Coastal and Marine Geology division of the USGS in Menlo Park, California. Bill worked on many aspects of marine geology throughout his career but what he is perhaps best known for is the exploration and investigation of deep-sea sedimentary systems (submarine fans). Bill was among the first to characterize the sedimentology and geomorphology of turbidite fans and to propose conceptual models of their occurrence and evolution.

There are many people that I could call a “hero” but one that had a significant influence on me is marine geologist Bill Normark (1943-2008). Bill spent the majority of his career with the Coastal and Marine Geology division of the USGS in Menlo Park, California. Bill worked on many aspects of marine geology throughout his career but what he is perhaps best known for is the exploration and investigation of deep-sea sedimentary systems (submarine fans). Bill was among the first to characterize the sedimentology and geomorphology of turbidite fans and to propose conceptual models of their occurrence and evolution.

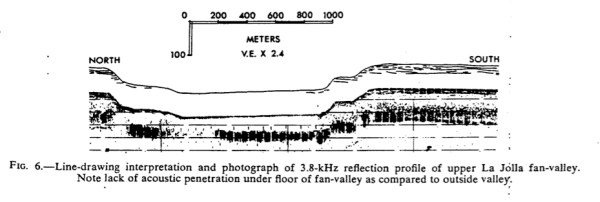

Bill’s early publications (late 1960s-early 1970s), especially the 1970 paper on submarine fan growth patterns, are now among the publications that any turbidite researcher must read and re-read. The image below is a figure from that paper. It shows data from a seismic-reflection profile and, in this case, reveals the cross-sectional geometry of a submarine fan valley.

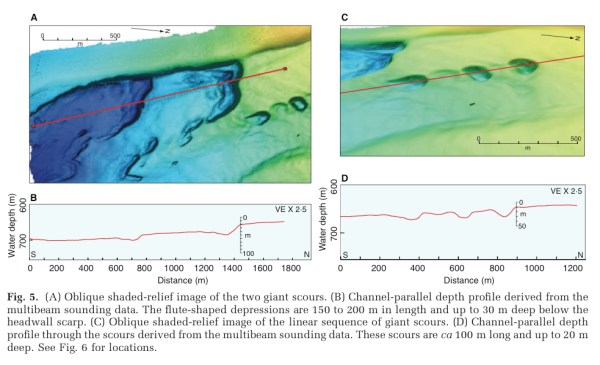

The quality of these data may seem pretty limiting compared to the cutting-edge multibeam bathymetric data of today, which is a testament to the strength of Bill’s insights from those days. But this was cutting edge at the time. Which brings me to one of Bill’s qualities that put him within a class of highly influential scientists — he never stopped utilizing the latest tools and technologies to do his science. Bill didn’t just have a few high-impact papers from his early work — he continued to innovate and publish throughout his entire career. For example, in the last few years of Bill’s life he hooked up with scientists and engineers at Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) to use their state-of-the-art Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) to map the sea floor at unprecedented resolutions. In fact, Bill’s last first-authored paper, which ended up coming out several months after he passed away, uses the data from this tool to investigate details of sedimentary processes (image below).

High-resolution bathymetric data of deep-sea erosional scours acquired by Bill Normark using MBARI's AUV system (credit: Fig. 5 of Normark et al.; Sedimentology, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2009.01052.x)

Bill also had great respect and admiration for his predecessors and mentors. He encouraged us to read the old papers, monographs, and books from deep-sea mapping pioneers of the early 20th century. Bill held special reverence for one of his mentors, the great marine geologist Francis Shepard and was very honored to receive the Society for Sedimentary Geology’s Francis Shepard Medal for excellence in marine geology in 2005.

Bill’s influence on my own research and development as a geologist has been profound. Before collaborating with Bill my experience was almost wholly with ancient deep-sea systems preserved in the stratigraphic record (especially outcrops). Bill’s marine geologist point of view — studying modern and geologically recent systems — has led to my interest in integrating observations from the ancient and the modern. One of the seminal papers in turbidite research (and required reading for anyone in this field) is from Bill and outcrop geologist Emilano Mutti in 1987*. In this paper they present a comprehensive discussion of the values and challenges associated with comparing results from ancient and modern studies. It’s one of those papers that when I re-read I gain yet another nugget of insight. I think that trying to bridge the gaps in our understanding of these processes as gained from modern vs. ancient studies is a worthy endeavor and Bill is an inspiration in that regard.

Because the Menlo Park USGS office is close to my PhD alma mater and we were also researching deep-sea sedimentary systems, Bill ended up serving on my and several others committees. A few of us ended up collaborating very closely with Bill — spending a lot of time with him and using USGS data and resources for our projects. One of the last papers Bill worked on before he lost his battle to cancer was a major component of my Ph.D. dissertation (published last year in GSA Bulletin; pdf). This project was a true collaboration in that it was based on a lot of data and information Bill had investigated in the past combined with some of my own ideas and questions. Bill was a great mentor in that respect — he was patient and encouraging, letting us figure things out on our own while also providing guidance.

Finally, Bill was simply an awesome person. His enthusiasm was infectious and he was always thinking and looking forward. The whole time I knew and worked with Bill he was battling cancer and his energy and interest was still greater than most. Bill was also an accomplished wine maker. He brought the diligence and attention-to-detail he used in his science to the wine-making process, which resulted in being awarded some medals in prestigious California wine competitions in the mid-2000s.

Bill is sorely missed by his family, friends, and colleagues but his accomplishments and influence will be with us for a very long time.

–

* Mutti, E., and Normark, W.R., 1987, Comparing examples of modern and ancient turbidite systems; problems and concepts, in Legget, J.K., and Zuffa, G.G., eds., Deep Water Clastic Deposits: Models and Case Histories: London, Graham and Trotman, p. 1–38. tion 10, p. 75–90.

Other articles about Bill Normark:

(1) Short biography, including list of scientific accomplishments, from the USGS for more information about Bill Normark’s career: http://soundwaves.usgs.gov/2008/06/staff.html

(2) A memorial written by my colleague, Andrea Fildani, published in AGU’s EOS newsletter in May 2008: http://www.agu.org/pubs/eos/eo0822.shtml (scroll down to see link to PDF)

Friday Field Foto #109: Yosemite granite

This week’s Friday Field Foto is from a weekend trip I took last month to Yosemite National Park. I’ve been trying to broaden my photo collection with more than just sedimentary rocks … so today is a close-up of some beautiful Yosemite granite. Now that I think about it, I’m assuming this is granite — if some igneous nerd wants to inform me that this is actually a granodiorite or whatever, please do!

You can see more photos of Yosemite on my Flickr page.

–

Happy Friday!

Papers I’m Reading — April 2010

It’s been a busy few weeks, I’m not reading as much as I should be; here is this month’s installment in the papers I’m reading series:

- Palinkas, C.M., et al., in press, Observations of event-scale sedimentary dynamics with an instrumented bottom-boundary-layer tripod: Marine Geology, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2010.03.012. [link]

- Paull, C.K., et al., in press, The tail of the Storegga Slide: Insights from the geochemistry and sedimentology of the Norwegian Basin deposits: Sedimentology, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2010.01150.x. [link]

- Omura, A. and Ikehara, K., in press, Deep-sea sedimentation controlled by sea-level rise during the last deglaciation, an example from the Kumano Trough, Japan: Marine Geology, doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2010.04.002. [link]

- Denlinger, R.P. and O’Connell, D.R.H., 2010, Simulations of cataclysmic outburst floods from Pleistocene Glacial Lake Missoula: GSA Bulletin, doi: 10.1130/B26454.1. [link]

–

Note: the links above may take you to a subscription-only page; as a policy I do not e-mail PDF copies of papers to people (sorry).

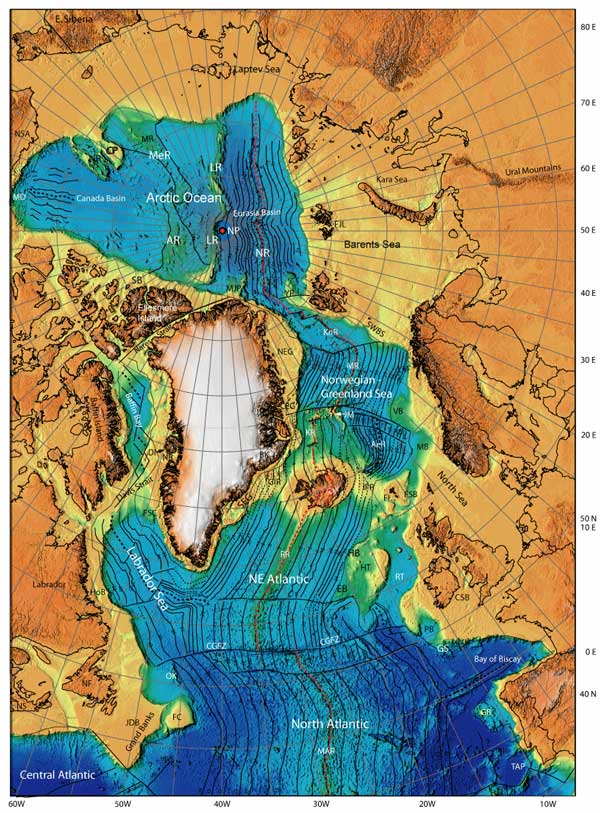

I’m using this week’s Sea-Floor Sunday to show a few simple maps of the region around the erupting Eyjafjallajokull volcano in Iceland. I don’t have a photographic memory of the Earth’s surface so I always like to remind myself what a region’s topography/bathymetry looks like.

The first image (below) is a regional map centered on Iceland. I found it on this article on the mantleplumes.org site.

North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans and surrounding regions (credit: http://www.mantleplumes.org/Iceland2.html)

The next one is from GeoMapApp and simply shows the position of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Iceland, and Eyjafjallajokull.

Here is a nice perspective bathymetric image (found here) showing the relationship of Iceland to Great Britain, the North Sea, and Scandinavia.

Perspective bathymetric image of the Nordic Seas (credit: http://folk.uio.no/bjorng/tidevannsmodeller/tidemod.html)

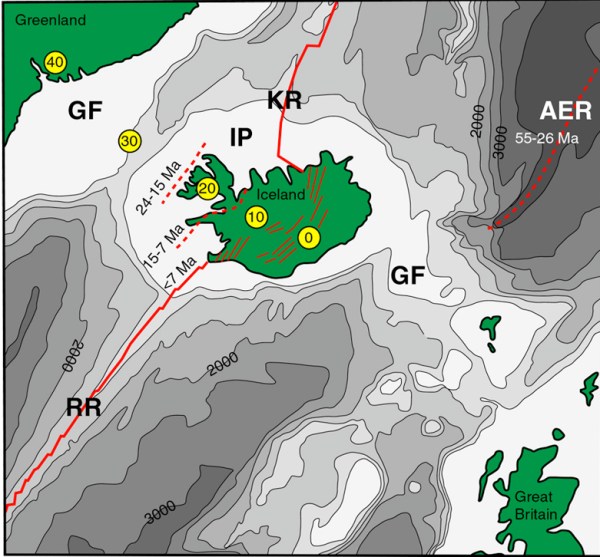

While searching for images I came across a great site from Tobias Weisenberger that, among many other topics, included a page on the geology of Iceland. If you want to learn more about the origin and evolution of this area I recommend it. The image below shows the bathymetry in relation to the age of the Iceland plume (yellow dots in millions of years) and the active rift zones (red lines).

Bathymetry around Iceland, active rift zones, and age of Iceland plume (credit: http://www.tobias-weisenberger.de/6Iceland.html)

Although not a bathymetric image I figured I’d throw in this simplified geologic map (also from Weisenberger’s site). Note location of Eyjafjallajokull near the southern tip of the island.

As I mentioned in my post on Friday (showing a video of a jökulhlaup) check out the Eruptions blog and The Volcanism Blog for continuing coverage of this geologic event.

The ongoing eruption of the Eyjafjallajokull volcano in Iceland is making big news because of the effect of the ash on flights in northern Europe. My two main sources of information, the Eruptions blog and The Volcanism Blog, both do a great job of not only relaying up-to-date information but providing tons of links to various scientific organizations reacting to and studying this geologic event.

I wanted to highlight this video I came across showing a jökulhlaup in process. A jökulhlaup is the Icelandic word for a glacial outburst flood that is commonly generated by subglacial melting during a volcanic eruption. I think the term is also used for similar magnitude flood events from glacial lakes when an ice (or debris) dam abruptly fails.

Absolutely amazing.

I also want to point out the train of waves from 0:46-0:57 seconds in the video. I’m not sure — don’t quote me on this — but those appear to be associated with supercritical flow (most are introduced to this concept discussing the formation of antidunes). Perhaps a train of hydraulic jumps or some kind of cyclic step process? A quick search came across this paper interpreting supercritical flow based on the sedimentary deposits from a jökulhlaup in 1918 in Iceland.